Paul Ryan and the Cycle of Compassionate Conservatism

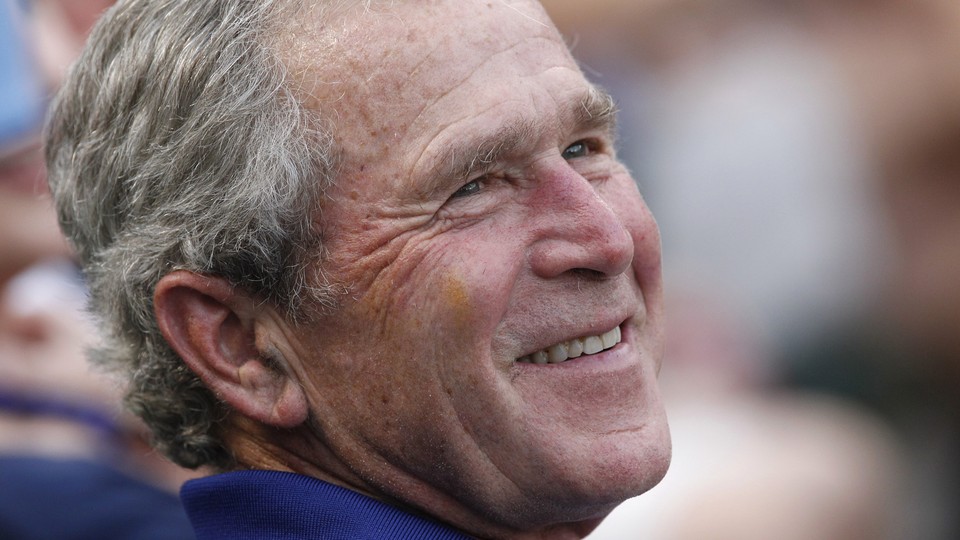

Republicans are trying to borrow George W. Bush's 2000 playbook, but is that really going to work?

Over the past two decades, since the 1992 presidential election, Republican politics has followed a cycle. It goes like this:

We’re now back at Stage Six.

In the late 1990s, after Bill Clinton campaigned for reelection against the Gingrich Congress’s assault on government spending, George W. Bush decided that he too would make congressional Republicans his foil. In September 1999, when GOP budget hawks tried to cut the earned-income tax credit, the Texas governor declared, “I don't think they ought to balance their budget on the backs of the poor.”

Now the same pattern is repeating itself. In 2012, Mitt Romney boasted that he was “severely conservative.” He chose Paul Ryan as his running mate in large measure to mobilize Republicans who loved Ryan’s assault on the welfare state. But Romney and Ryan lost in part because Barack Obama, like Clinton before him, scared Americans about the GOP’s assault on government. Moreover, as in the late 1990s, the budget deficit is going down.

As a result, potential GOP presidential candidates are falling over one another to run as Bush did in 2000: as compassionate conservatives. Rand Paul is arguing for shorter prison sentences. Republican Governors John Kasich and Mike Pence are expanding Medicaid. Marco Rubio recently said it was time for Republicans to stop trying to balance “the budget by saving money on safety-net programs.” Even budget cutter extraordinaire, Paul Ryan, wants to “remove it [the fight against poverty] from the old-fashioned budget fight.”

It's easy to see why compassionate conservatism is back. It’s harder to see it helping Republicans all that much.

First, it didn’t even help Bush all that much. Let’s remember, he won less than 48 percent of the vote in 2000. Between them, Al Gore and Ralph Nader won more than 51 percent. Exit polls that year found that of the 10 qualities Bush voters cited as reasons for voting for him, “cares about people like me” was number seven. In 2004, pollsters asked the question differently. As Ben Domenech has noted, Bush won only 24 percent of voters who said their top priority was a candidate who “cares about people.” He won only 23 percent of voters who said their biggest concern was health care. That’s better than Mitt Romney, who won only 18 percent of voters who prioritized “car[ing] about people.” But it’s exactly the same as John McCain’s percentage in 2008. And on health care—a key domestic-policy issue on which Republicans want to show they’re not hard-hearted—Bush in 2004 did slightly worse than McCain and Romney.

The big reason Bush won in 2004 isn’t because he wowed voters with his compassion. It’s because he won 86 percent of those who said their number one concern was “terrorism” and 80 percent of those who prioritized “moral values.” Since then, national security has faded as a political issue and the GOP’s historic advantage on it has disappeared. Something similar has happened on the culture war, which has shifted in the Democrats’ direction because gay marriage—which Bush won votes for opposing in 2004—is now far more popular.

If the first problem with running as a compassionate conservative is that it didn’t work so effectively for George W. Bush, the second is that being seen as compassionate is probably harder for a Republican today. Suspicion of the GOP among key demographic groups is greater, and the Republican base is less tolerant of reaching out to them. When Bush was president, the leaders of both parties opposed gay marriage. Now it’s a partisan issue, which makes it harder for a Republican candidate to win LGBT votes, at least without provoking a rebellion among the GOP’s Christian conservative base.

It’s the same with Hispanics. Bush won 35 percent of the Hispanic vote in 2004, but since then Hispanic have become more alienated from the GOP. The activist right’s fury over illegal immigration has deepened, which means that compared to the Bush years, a Republican presidential candidate will have more suspicion to overcome and less political flexibility with which to overcome it.

Finally, the ranks of the demographic groups Republicans are targeting with their compassion crusade are more numerous. By 2016, Hispanics will represent more than double the share of the American electorate they represented in 2000. That means even if a Republican won 35 percent of the Hispanic vote, as Bush did, the consequences would be more dire, since his Democratic opponent would have won 65 percent of a higher number.

Then again, if history is any guide, stage seven of the Republican cycle is that a presidential candidate professing compassionate conservatism loses the popular vote by a half-million votes but is handed the presidency by the Supreme Court. The way the Roberts Court has been acting, I wouldn’t rule it out.