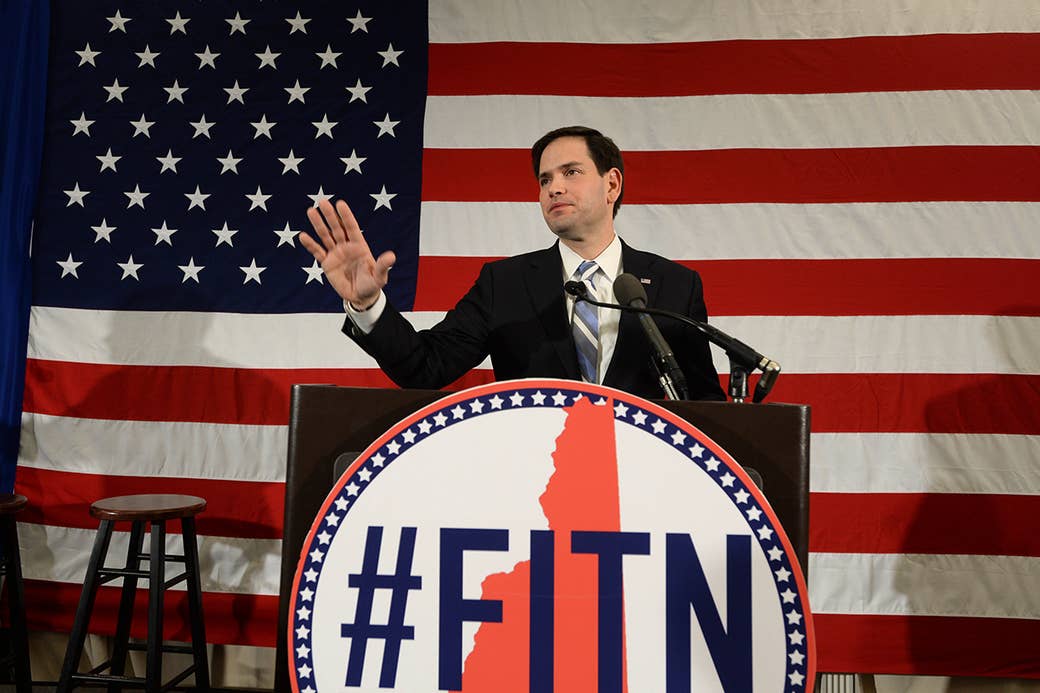

Ever since a right-wing backlash blew up the bipartisan immigration bill that Sen. Marco Rubio helped champion in 2013, the ambitious Republican has struggled to find his political footing on the issue. For two years, he has hemmed and hawed; ducked and dodged; retracted, retreated from, and repeatedly revised his immigration rhetoric in a ploy to appease conservative activists without fully forsaking his position. These days, when the subject comes up in town hall meetings or TV interviews, the silver-tongued senator — now officially running for the GOP presidential nomination — is often reduced to reciting a few stilted talking points, and then angling to change the subject.

But there is one setting where Rubio frequently and unabashedly touts his immigration record to great effect: closed-door meetings with the GOP's elite, high-dollar donors.

According to a half-dozen Republican fundraisers and contributors who have been courted by the Rubio camp, the candidate's aggressive advocacy for the Senate's 2013 immigration bill has proved to be a substantial draw within the GOP money crowd — and his campaign has shown little hesitation about cashing in. Even as Rubio labors to publicly distance himself from the legislation so loathed by conservative primary voters, he and his aides have privately highlighted this line in his resume when soliciting support from the deep-pocketed donors in the party's more moderate business wing.

Norman Braman, the 82-year-old auto tycoon who has reportedly pledged to spend as much as $10 million to get Rubio elected, told BuzzFeed News that he and the candidate have bonded over immigration. Not only do they agree on the policy specifics, but at a deeper level the issue is a personal one for both of them.

"He's a first-generation immigrant, and I'm a first-generation immigrant. I can relate to that," said Braman, whose Jewish parents emigrated from Europe. "Some type of immigration reform has to come about because it's too great a problem. And we agree on that. He believes we have to secure the borders first, and I believe we have to secure the borders first."

The Miami billionaire added that he's known Rubio for a long time and always liked him, but that the senator's dedication to taking on the messy immigration battle in Congress — particularly while so many other Republicans shied away from the fight — demonstrated his White House worthiness. "Isn't that what leadership is all about? … Marco is not the type of person in all the years that I have known him who will put his finger up in the air to determine which way the wind is blowing."

Similarly, George Seay, a wealthy investor who held a fundraiser for Rubio Tuesday night at his home in downtown Dallas, said the candidate's controversial work on immigration reform is a plus in his book.

"I mean, honestly, we've got some severe immigration issues that need to be addressed in this country," he said. "It's been used for political gain by people who don't want to solve the problems. I find that incredibly irritating. On that issue, and many other issues, I think Sen. Rubio has shown a level of courage that most politicians lack."

Seay stressed that he didn't speak for the candidate or those who attended his fundraiser, but he said Rubio's personal story and agenda — particularly his work on fixing the U.S. immigration system — is especially compelling in a state like Texas, with its shared Mexican border and sprawling population of Latino immigrants. "He's a living embodiment of their dreams," Seay said. "They come here because they want a safe life for their children and grandchildren, they want economic opportunity, they want to be able to work hard."

It isn't only committed Rubio donors who are swooning after hearing the candidate's immigration spiel. During a press call in February with other pro-immigration figures in GOP fundraising, California-based fast food CEO Andrew Puzder said that regardless of whatever public murkiness might surround the senator's position, Rubio had personally assured him he was still dedicated to the cause.

"I actually have spoken with Sen. Rubio on the issue and he has not backed away from wanting immigration reform at all," Puzder said. "He does think it's very difficult to do it unless you address illegal immigration first so there may be a step process to doing this. But he's still a very strong advocate for getting immigration reform that's effective and helps people, and he's one of the leaders in our party on this issue."

A spokesman for the Rubio campaign declined a request for comment. But granted anonymity, one adviser answered questions about these private conversations by saying, "Marco gives the same speech with donors that he does in public. He doesn't focus on immigration, but it almost always comes up in the Q&A in both public and private settings."

None of the donors who spoke to BuzzFeed News suggested immigration was the central or solitary selling point in Rubio's fundraising efforts. The senator's well-informed foreign policy tough talk holds special appeal to neoconservative hawks, while others are enthused by his reform-minded policy proposals — like a re-imagination of the high school education system that emphasizes vocational training and professional apprenticeships for students not interested in college.

But every source interviewed said that no matter how radioactive Rubio's immigration record might be to the right, it has done nothing but help him in this early stage of the primaries, when filling the campaign war chest is the chief concern. Two Republican fundraisers who have met with Rubio — requesting anonymity to candidly assess his efforts — even expressed surprise at how enthusiastic the candidate has seemed in private to promote his work on the Senate's immigration bill, given his strong reluctance to do so in public.

Rubio's hesitations are not politically unfounded. In early 2013, the young, Spanish-speaking conservative joined a bipartisan group of senators tasked with producing a sweeping legislative overhaul of U.S. immigration policy. A rising star in the GOP who was already surrounded by almost manic presidential speculation, Rubio promptly became the conservative face of the effort. The bill they eventually presented would have added tens of thousands of new border patrol agents, instituted tougher enforcement measures, revamped the U.S. visa system, and provided a pathway to citizenship for most of the estimated 12 million undocumented immigrants in the country. It passed the Senate but by the time it reached the Republican-controlled House, talk radio crusaders and conservative activists were ferociously waging war on the legislation — as well as Rubio, the Tea Party turncoat who had betrayed the movement with his support for so-called "amnesty."

Rubio's favorability ratings collapsed among national Republicans, and he was unceremoniously defenestrated from the top tier of the 2016 field. He was soon furiously backpedaling on his support for the doomed bill, and before the year was out he was actively calling for the House to kill it. That perceived flip-flop, of course, confirmed the long-held suspicions of left-leaning immigration activists who believed his brief dalliance with their mission was solely about politics. The animosity between the two camps hasn’t dampened: Earlier this month, DREAMer activists marched on the Miami site where Rubio was officially announcing his presidential campaign, loudly chanting, "Undocumented! Unafraid!"

Rubio, meanwhile, has insisted that he did not reverse his position at all. His rhetorical defense has undergone several small evolutions over the past two years, but his fundamental argument was on display last week when CBS News journalist Bob Schieffer interviewed him on Face the Nation. The candidate said he remains committed to the broad tenets of the original immigration bill, but the 2013 fiasco convinced him that the legislation should be passed in small, bite-size chunks.

"If you became president, would you sign the bill that you put together into law?" Schieffer asked him.

Rubio's body stiffened. "Well, that's a hypothetical that will never happen," he said, leaning rigidly forward in his chair like a nervous pupil.

He went on to explain that as president he would first ask Congress to pass a "very specific law" that cracks down on illegal border-crossers and visa-overstays; then he'd want a bill making the legal immigration system "less family-based, more merit-based.” Finally, once those were in place, he would request legislation to deal with the country's 12 million undocumented immigrants. As he talked through these bullet points, he framed them — as he often does — as a more pragmatic, realistic alternative to the large, unwieldy legislative monstrosity of 2013.

But, of course, Republicans may not retain their majority in the Senate, and it seems incredibly unlikely Democrats would help pass a standalone border security bill without any concessions. And on the 2016 front, it's an open question whether Latino voters will flock toward a presidential candidate peddling such a plan.

In reality, said one Republican fundraiser, Rubio isn't currently focused on effective legislating or courting independent Latino voters. He is simply trying to find a message that can navigate between the monied elites at his fundraisers and the conservative voters in Iowa.

His dilemma is emblematic of just how deeply the immigration issue has divided the Republican Party's conservative base from its elite donor class. Among the wealthy establishment figures who write six- and seven-figure checks to political action committees, there is overwhelming support for softer immigration laws. The reasons for the split range from culture to ideology to economic interests. Whereas the well-heeled entrepreneurs, investors, and Fortune 500 executives who populate the GOP's business wing often stand to profit from access to legal, low-income labor, middle-class conservatives are more likely to fear negative effects from immigration. In a poll released last summer, Pew found that 73% of people identified as "steadfast conservatives" saw immigrants as a "burden," while just 21% of higher-income voters identified as "business conservatives" agreed.

But among those fundraising rainmakers most deeply invested in getting a Republican president elected, the predominant arguments for more progressive immigration policies often revolve around electoral math.

"Winning a Republican presidential campaign is very, very hard,” said Spencer Zwick, Mitt Romney’s 2012 finance director, during the same pro-immigration press call in February. “And I feel like one of the things we do to ourselves as Republicans is at times we make it harder than it needs to be."

Zwick would know: In 2012, Romney tacked hard to the right on immigration in order to win the primaries, only to pay the price on Election Day when he attracted just 27% of the national Latino vote. Even if Tea Partiers aren't willing to get on board, Zwick said the GOP money men have learned their lesson: "I really believe that the donor community… now finally recognizes, and I see them only wanting to get behind a candidate that is willing to take leadership on his issue."

Though Rubio languished in single digits nationally for a long time, there are significant signs that he’s earning a fresh look from many of the conservatives who abandoned him in 2013. He has one of the second-highest favorability rating in the likely 2016 field, and only 11% of Republican voters believe he is "not conservative enough."

Rubio's deft ability to lure back conservative voters without actually giving up his immigration position has impressed many in the Romney donor network, according to one former fundraiser for the nominee.

"I think Rubio's kind of getting the advantage of [donors] assuming he's somewhat moderate on the issue," the fundraiser said. "There's a lot of donors and contributors who liked his initial positions... But he's walked it back in a way that seems to satisfy the conservative base."

The fundraiser hastened to add that he doesn't believe Rubio is necessarily making contradictory statements about immigration to different audiences — the candidate is too "disciplined" to take such a risk. Instead, Rubio is carefully calibrating his approach to suit the setting. And after watching their party's 2012 nominee spend month after miserable month clumsily attempting to sell his moderate record to a permanently suspicious contingent of conservative voters, some in the GOP donor class are encouraged by Rubio's political dexterity. "He’s really talented in that way," said the fundraiser.

Still, the Rubio campaign adviser suggested that in at least one respect, his candidate may have learned a valuable lesson from the 2012 nominee — namely, not to try to get too slick during these closed-door donor meetings.

"His answer is always the same," the adviser said of the immigration-related questions Rubio fields from donors. "With a camera phone in every pocket, is there really such a thing as a 'private' setting in 2016?