San Francisco, April 28

Hayes Grier is hungry. It’s well after 9 p.m., after a two-hour show and a long day, and the dinner delivery guy is running late, and the 14-year-old’s face is starting to get that wild-eyed, slightly manic look that was all but invented by overstimulated and underfed teenage boys. He can’t sit still but has nowhere to go, so he paces around the narrow green room in San Francisco’s Regency Ballroom, chewing gum and scrolling through his Twitter mentions, which stack up at a rate of dozens, sometimes hundreds, per minute. If you listen closely, you can hear the chatter of 2,000 or so fans, nearly every last one of them a teenage girl, as they spill out of the venue and into the street. But Hayes is single-minded, desperately rooting around the green room for something, anything, to eat. He finds a pack of fruit snacks and tears into them, never once glancing up from his phone.

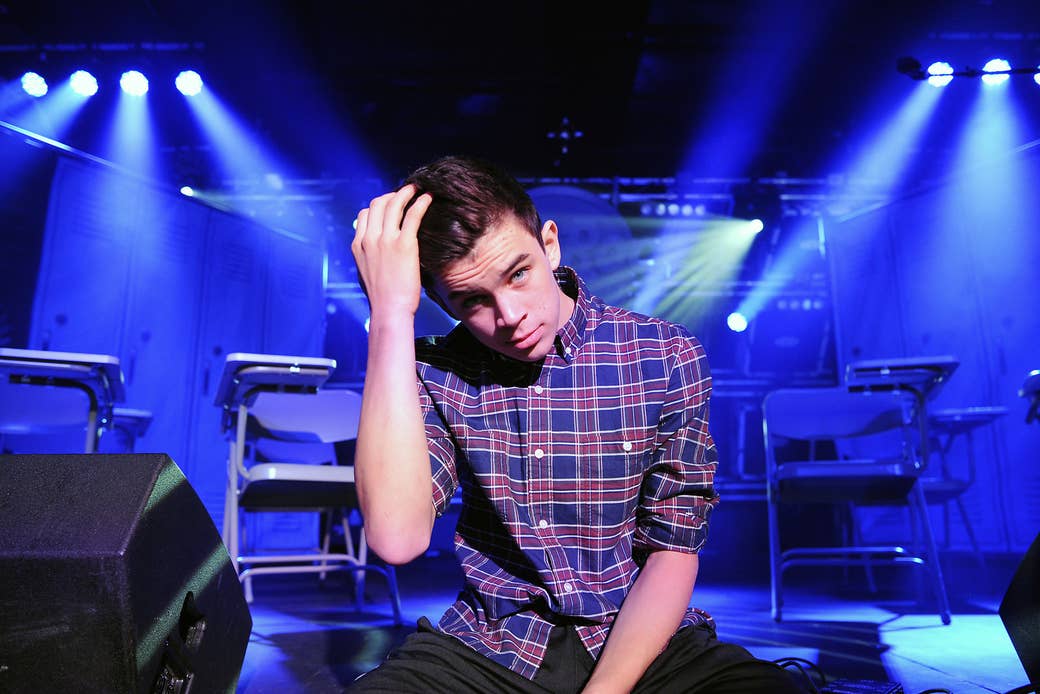

With full lips, Bieber bangs, and piercing blue eyes, Hayes has the unsalted-butter looks of the love interest on a CW show or the villain in a John Hughes movie. He dresses in the superficially alternative but fundamentally nonthreatening uniform popularized by Urban Outfitters and adopted by every (white) Cool Guy in every high school in America: jeans, skate shoes, graphic T-shirt or baggy tank top with the armholes cut low. He speaks slowly and indistinctly, with a soft North Carolina accent. He has beautiful teeth.

Hayes is one of the world’s biggest social media celebrities — a distinction that, in 2015, isn’t necessarily so far from that of one of the world’s biggest celebrities, full stop. He has a bevy of lucrative endorsement deals, a fashion collaboration with Aeropostale, a packed touring and appearance schedule, and upwards of a million followers on each of the half dozen or so social networks he uses. It helps that his 17-year-old brother, Nash, is arguably the most famous Viner on the planet, with nearly 12 million followers and more than 2.8 billion lifetime loops on the platform.

But the younger Grier’s star is rising swiftly in its own right: His Instagram account, whose shirtless pics and up-close selfies rocketed him to fame less than two years ago, has roughly as many followers — 3.9 million — as those of Neil Patrick Harris and Michelle Obama combined. All told, his Vines — which tend toward Jackass-lite stunts, innocuous physical comedy, and brief snapshots of life on tour — have been looped more than 300 million times. At this point, the Grier brothers are so famous that they can’t go to a mall or amusement park or high school football game without being mobbed. They are so famous that the rest of their family has become famous too, osmotically and apparently without even trying: At the L.A. stop of the tour we’re currently on, dozens of girls (and a not-insignificant number of moms) clamored to take pictures with their father, Chad, better known as “Dad” to many of the fans. Hayes and Nash’s half sister, Skylynn, who’s frequently featured in their videos and photos, has more than 1.3 million Vine followers. She’s 5.

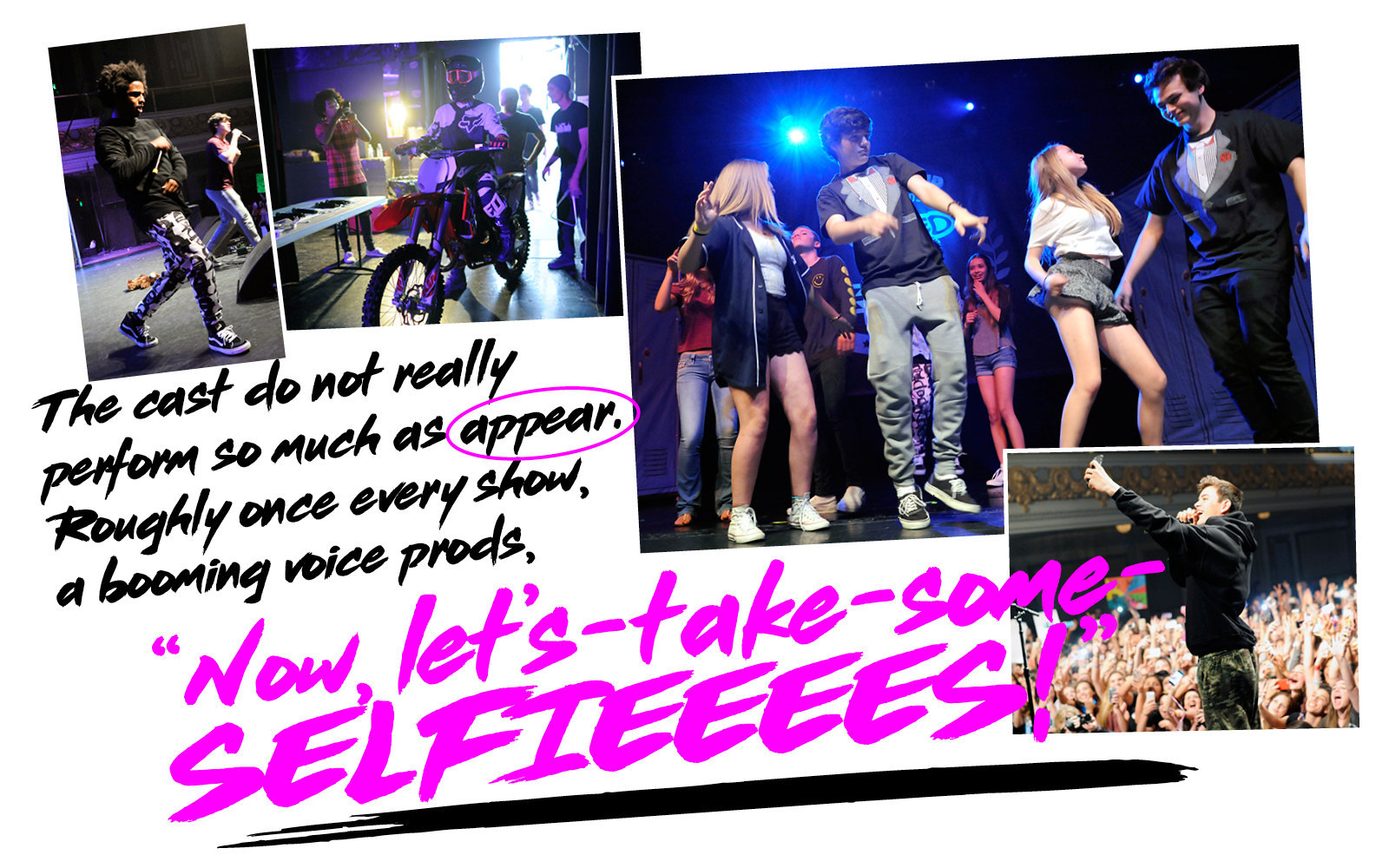

And though this evening’s show, stop number five on a hugely popular 18-city bus tour thrown by a young and lucrative company called DigiTour, featured six other performers — five boys and one girl, each of them social media stars as well — Hayes was clearly the biggest draw. At the show, dozens, if not hundreds, of girls wore bright-red T-shirts emblazoned with his name on them in a blocky, football-jersey-style font, on sale at the merch table for $30 each. When he took the stage — rolling in on a dirt bike that he then dramatically dismounted, tossing those Bieber bangs back as he removed his helmet — the Regency erupted into an otherworldly roar that somehow managed to combine the upper-register shriek of a teakettle coming to boil and the solid, full-body wallop of a moving train coming very, very close to you. The girls rushed forward, mouths open and phones aloft. One burst into wild, jagged, wracking sobs.

Beyond the dirt bike stunt, Hayes doesn’t do much during the half hour or so he spends onstage. Though several DigiTour-ers harbor musical ambitions (and, in most cases, the talent to realize them), beyond moderate charisma and those pop idol looks, Hayes doesn’t seem to — or even purport to — have any of the qualities that one might equate with sell-out-a-theater stardom. He doesn’t sing or act or play an instrument or tell great jokes or even play sports exceptionally well; he just is, and that is far more than enough. As Meridith Valiando Rojas, DigiTour’s 30-year-old CEO, explains later, “Some of these kids, their talent is relating to their audience. They’re the coolest people you know, and they happen to have 5 million friends.”

Perhaps for this reason, the DigiTour show itself seems mostly designed to enable the boys to mug for the crowd as much as possible and the crowd, in turn, to scream as much as possible. All told, it feels less like the kind of event you’d expect to nearly sell out a massive ballroom than it does a summer camp talent show, running through a sort of cartoon version of a typical day at a typical high school in a typical town: First, there’s homeroom (introductions), lunchtime (food fight), cheerleading practice (a goofy, strutty dance sequence set to Gwen Stefani’s “Hollaback Girl”). And then, of course, the denouement: prom, during which six girls and one boy are plucked from the audience and matched with a cast member for an onstage slow dance set to Wiz Khalifa's summer funeral banger "See You Again." Between these bits, the more musically oriented cast members sing, covering songs by nostalgia or Top 40 pop acts such as Journey and Drake. Four of the kids do a Fallon-style lip-synch battle, and Hayes and another cast member, Tez Mengestu, rap along sputteringly to Rae Sremmurd’s “No Flex Zone.” But by and large, the cast do not really perform so much as appear. Roughly once every show, a booming voice prods, “Now, let’s — take — some — SELFIEEEES,” in the way another announcer might implore a crowd to make some noise. The fans oblige.

Last year, according to Valiando Rojas, DigiTour sold 120,000 tickets for 60 shows. (In 2013, they sold 18,000.) This year, it’s on track to more than double last year's numbers. Nearly as soon as this tour is over, a slightly new arrangement of stars will gather for DigiFest, a six-city outdoor festival circuit that Valiando Rojas calls “Coachella for the YouTube generation.” After that, a new iteration of DigiTour, with different talent and different tour stops, will rev up: The cycle is endless, because the demand is bottomless. Though Valiando Rojas declined to reveal exact revenue figures, industry estimates suggest that DigiTour will bring in up to $20 million this year.

Other than the dads, who tend to huddle near the bar, exchanging looks of befuddled resignation, there are less than a dozen boys at each show. DigiTour is manifestly, happily, a place for girls — about 95%, mainly between the ages of 10 and 18 — and for a particularly girly-feeling, completely un-self-conscious kind of fandom. It’s a kind of fandom with no irony and no limits, a kind of fandom that seems to be almost exclusively practiced by people old enough to understand the vector of their desires but young enough not to be embarrassed by them.

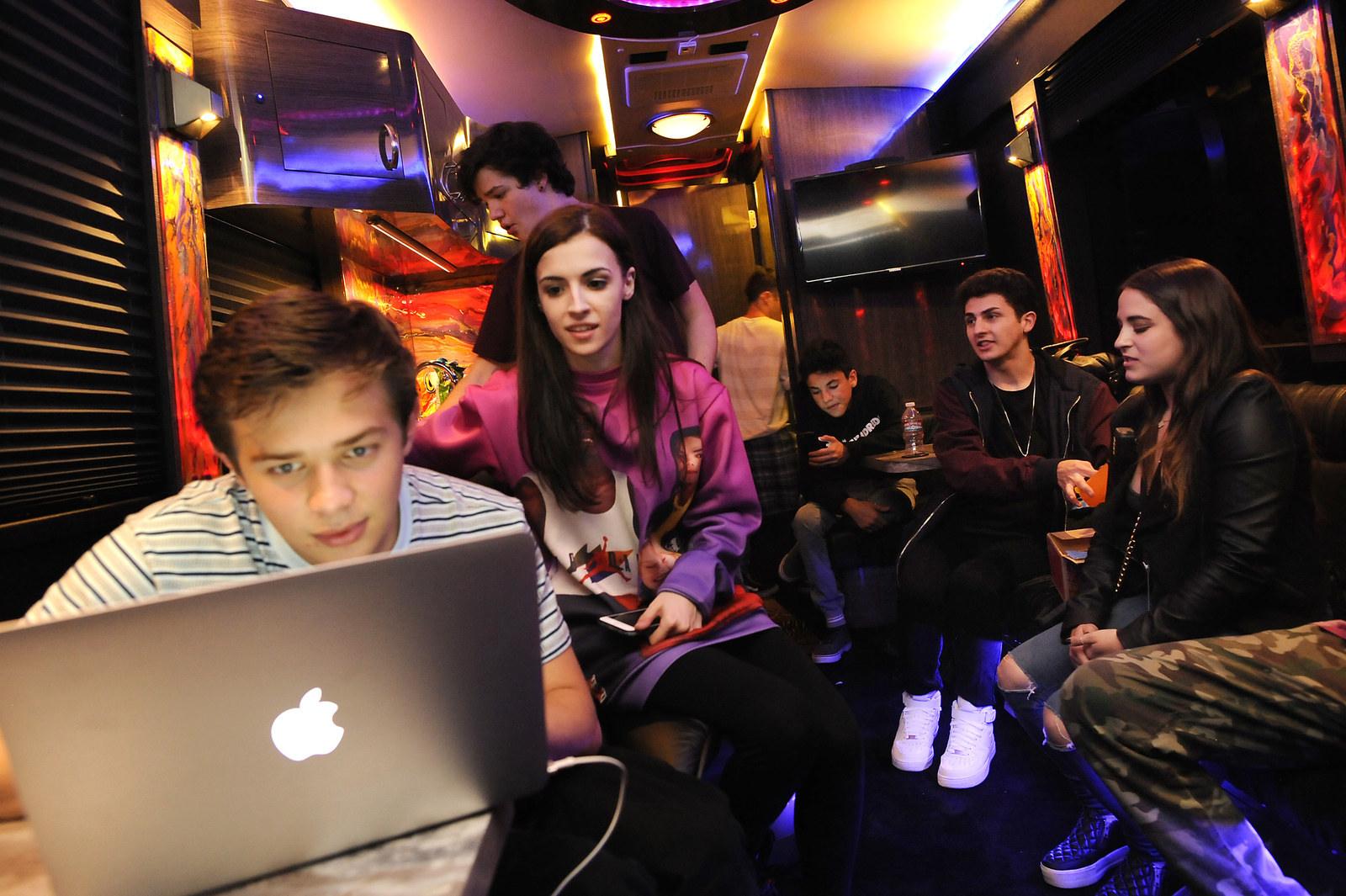

The show ends, as it always does, with a group number, all seven cast members onstage singing a song by fellow social media stars Jack and Jack, arms around one another's shoulders. And then the floor lights come up, and the fans stream out, and the kids head backstage to wait as the crew packs up and prepares for the overnight drive to L.A. Alec Bailey, an 18-year-old from North Carolina who hopes to use this tour to kickstart a contemporary-country music career, fiddles with his new Polaroid camera. Alyssa Shouse, 19, a YouTube singer and the tour’s only girl, sips water — she’s had a brutal sore throat all day. Daniel Skye — a very young-looking 14-year-old from South Florida — strums a guitar. They chew Sour Bubble Tape and look at their phones and sift through the gifts tossed onstage and nervously passed off by fans: stuffed animals, letters, candy. Finally, at around 10, dinner — burgers and fries delivered from the diner around the corner — arrives at the Regency, and the kids abscond to their tour bus to eat it.

The bus is so comically close to what you might imagine a tour bus full of teens would look like that it almost feels set-dressed. In the narrow, couch-lined area that serves as something of a rec room on wheels, a Costco-grade box of Cinnamon Toast Crunch rests on a counter next to a bottle of vitamin C (everyone on tour “gets sick basically constantly,” a handler explains). A basket of fruit sits heroically on a table, untouched. A beach ball has, somehow, managed to become wedged between a cabinet and the ceiling. Farther back is the narrow bank of triple-decker bunk beds that serve as claustrophobic sleeping quarters for the kids and the handful of twentysomethings that serve as their chaperones-slash-bodyguards-slash-assistants. Beyond that, there’s another set of couches. I am told they play a lot of Mario Kart back there.

After spending four days with them and asking the question as many times and in as many ways as I could, it became clear to me that DigiTour’s talents do not fully understand their own appeal. Or perhaps that their appeal is exactly as simple as it looks. “They just like our videos, really,” Aaron Carpenter, another cast member, tells me backstage in Tucson. Aaron has more than 1.8 million followers on Instagram and gains about 4,000 a day, a figure he can recite from memory. “Like, there's not really any other way to explain it,” he continues. “It's like, uh, it's, like, a phenomena. I don't know. It's weird.”

“Teenage girls like to be obsessed with something,” Alyssa offers authoritatively. She is tiny, dark-haired, entirely sweet, and very pretty, with a Tinker Bell tattoo on her hip and a giant head. It’s not clear if she remembers that she’s technically a member of that group.

But for all this — the tour, the millions of followers, the stuffed animals and letters and candy — the kids don’t consider themselves famous, exactly. “[When] you can go somewhere and every single person is like, ‘Whoa, that's him’ — then you're famous,” explains Jonah Marais, a lanky 16-year-old with cornflower-blue eyes.

Yes and no. They don’t turn heads everywhere they go, but they are famous, at least among a small, very vocal group of people. But they don’t necessarily have mainstream followings or record deals or even Wikipedia pages. In some ways — from the outside, at least — it seems like the worst of both worlds: famous enough to have your life disrupted, not quite famous enough to reap all the perks. For now, the guys prefer the term “known.”

“Famous is like walking down the red carpet at the Grammys,” says Tez, a Vine star and childhood friend of the Griers. “I have followers on social media.” But what social media has done is decentralize celebrity and the celebrity-making apparatus, even while a tour like this employs familiar music biz tropes like long bus rides and screaming teenage fans. Rather than studiously following a worn path to fame, the kids get famous first, while a new infrastructure tasked with figuring out what to do with them gasps to catch up.

The girls are all enthusiasm, all the time. They line up for hours in the punishing, brittle heat of Los Angeles or Tucson or Las Vegas in the early spring, sweating off their makeup before they even enter the venue. They skip school for DigiTour, cash in their allowances for DigiTour, beg their parents to drive them hours from the suburbs to be at DigiTour. In Los Angeles, one will manage to get past security and sneak inside the venue; she will be discovered hours later, curled up under the stage. In Tucson, one fan will show up with two or three dozen apples, apparently inspired by an offhand tweet from Aaron about his appreciation for the fruit (“Apples are so underrated”). In Las Vegas, three of them will wake up at 3 a.m. and camp out behind the Hard Rock Cafe just to see the bus roll up in the dark.

But right now, it’s late and cold and they are mostly subdued, shivering in their brand-new T-shirts behind the barricade, hoping for a glimpse of the boys as they amble between the bus and the venue’s back door, hamburgers in hand.

“It’s my birthday,” one tells a security guard in a nakedly desperate bid to be let beyond the gate.

“Everybody says it’s their birthday,” the guard replies, unmoved. And then suddenly the buses shudder awake and roll down the hill, headed for Los Angeles, the girls waving goodbye long after they’re out of sight.

Los Angeles, April 29

Los Angeles is hot in that headachy, too bright way that only Los Angeles manages to be. We’re in direct sunlight. It’s just before 3 p.m., and the talent are preparing for the meet-and-greet portion of the show, which, today, takes place in a Spanish-style courtyard adjacent to Belasco Theater’s auditorium. Hayes’ father, Chad — stoic, broad-shouldered, very nice — stands off in one corner, reminding everyone to drink water. “I coach football,” he offers as explanation.

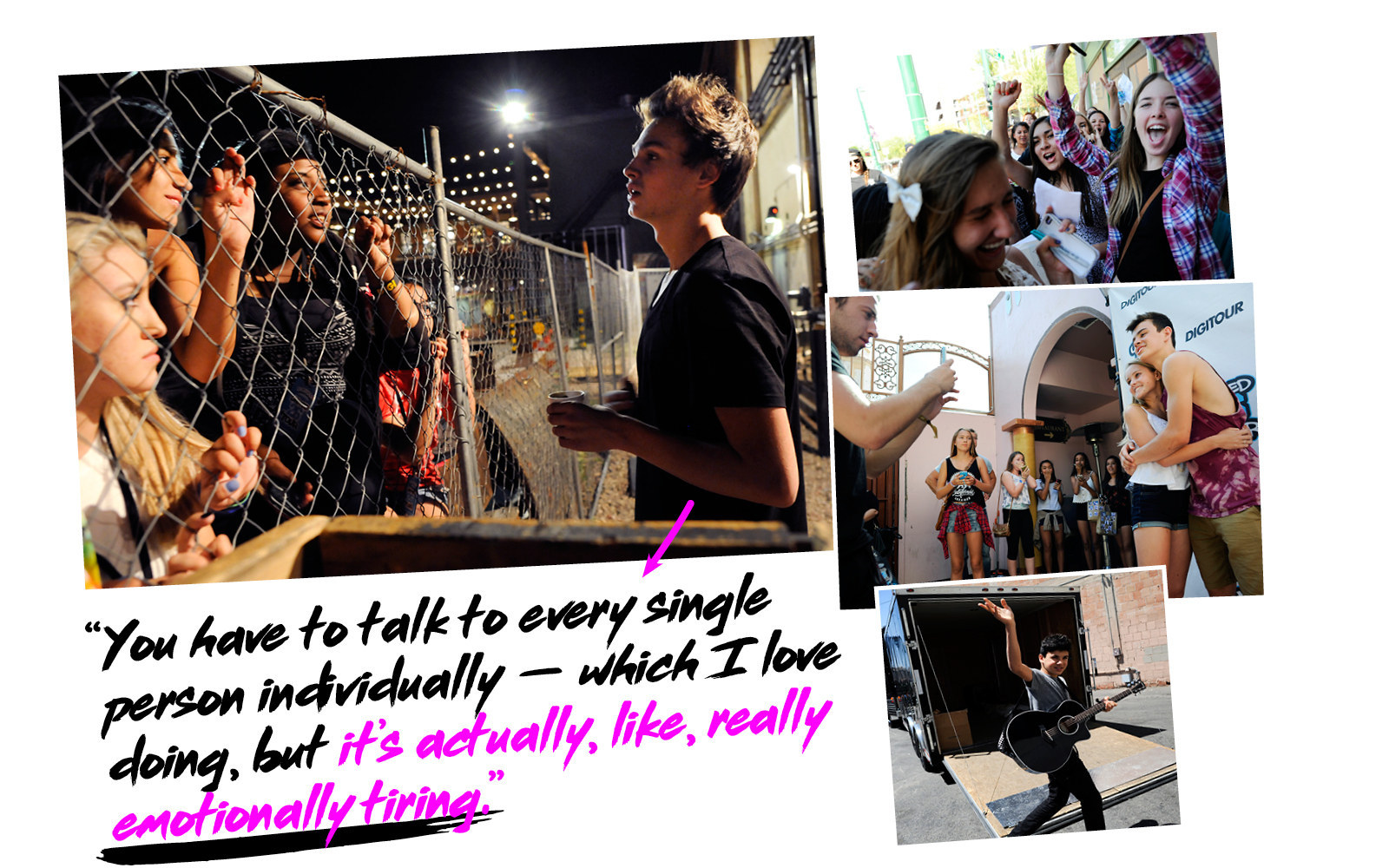

Basic DigiTour tickets run an allowance-friendly $25, but at $120 a pass, the meet and greet is the company’s cash cow, killer app, and flagship product: The company offers a couple hundred of these tickets at each show, and they typically sell out first. The meet and greet is organized essentially like an assembly line, except the object being produced is Instagram photos, on the order of thousands a night. The talent stands, receiving-line-style, ready for the stream of girls to go from one to the next. About three feet away, a parallel line of seven adults — most of them DigiTour staffers, one for each performer — stand ready to snap photos, passing the phones down the line on pace with their owners.

The interactions themselves are about 30 seconds long. First, the boy offers a greeting and, often, some kind of compliment. Sometimes the girls ask questions; sometimes they’re too stunned to say anything at all. The ones hoping to be discovered sing. Then there’s the picture: Most girls opt for a hug or a kiss on the cheek, but some go bigger and more theatrical — favored poses include boy behind the girl, hands around her waist, prom-style; hands clasped, looking into each other's eyes; forehead kiss; piggyback ride. The most ambitious fans try to leap into the boys’ arms (a practice discouraged by a black-clad DigiTour staffer who strolls up and down the line periodically yelling to that effect). Occasionally, they dive in for a kiss on the mouth.

And then repeat, and repeat, and repeat: 200 to 300 girls for each of the seven stars. The whole thing can take up to two hours and is mesmerizing to watch in the manner of any exercise — synchronized swimming, industrial food production — that is both spectacularly well-organized and also kind of on the verge of complete anarchy.

Daniel Skye (left) and Alec Bailey in Tucson, May 1, 2015

Alan Spiegel, CEO of 26, the management company that represents all seven of this particular tour’s talents, was turned on to what he calls “the influencer space” after a career investing in real estate and then tech, and upon seeing the success of some of the early social media stars. For someone like Spiegel, the appeal of a client like Hayes Grier is obvious: Social media is easy to consume, cheap to produce, and tends to spread in the organic, intimate way that advertisers covet.

And perhaps unsurprisingly, Spiegel, 31— who works, in part, to secure sponsorship deals between 26’s talent and companies such as Tommy Hilfiger, Coca-Cola, and Invisalign — sees digital as the great untapped advertising market. “It’s low-hanging fruit,” he says. “So much content is coming out of these guys every day and nobody is paying attention.” The least popular video on Nash Grier’s YouTube page — a single-take, dialogue-free 45-second teaser for his upcoming feature film debut, The Outfield — has more than 600,000 views, nearly as many as an average episode of Girls last season. The most popular has been viewed 11 million times.

26 was founded in March 2014, in partnership with Chad Grier and Spiegel’s brother Steven. (The name, according to Spiegel, is "a symbolic number that, numerically, in Hebrew, equals God's name. Our success has been really interesting, and God has a plan.") A little more than a year later, it has 15 clients, eight full-time employees, and a swiftly growing footprint in a swiftly growing industry.

According to Spiegel, a sponsored Vine from one of the 26 stable can fetch anywhere from $10,000 to $100,000. “We are witnessing this huge disruption,” Spiegel continues. “Whatever it is, this group has certainly captured that young millennial demographic, and been able to give them a constant amount of good content.”

Hayes Grier and Jonah Marais lounge around in the dressing room following the DigiTour show at the Rialto Theatre in Tucson on Friday, May 1, 2015.

Valiando Rojas details a similar conversion from old-school to digital media. A refugee from the record industry, she founded DigiTour with her husband, Chris Rojas, in 2010, a different era — Justin Bieber had managed to parlay YouTube fame into crossover success into international superstardom, but he was pretty much the only one to make the online-to-IRL transition.

So originally, the DigiTour audience wasn’t teenage girls at all but college-age internet subculture enthusiasts. “It was very niche,” she says. “Like Auto-Tune the News. Weird internet stuff.” But around 2013, after finding herself elbow to elbow with teenage girls at one of DigiTour’s shows, Valiando Rojas realized that “this was it — this was my audience.”

If, in 2010, the prospect of internet notoriety begetting genuine mainstream fame was enough to make Valiando Rojas’ peers in the music industry laugh, they’ve surely now accepted the new world order. Nash Grier, who is also represented by 26, has roughly 12 million Vine followers (three times as many as Justin Bieber); companies such as Virgin Mobile pay up to $100,000 for placement in one of his six-second videos. When Cameron Dallas, another Spiegel client, released Expelled, his first feature film, on iTunes last year, it immediately rocketed to the top of the digital download chart, briefly supplanting Guardians of the Galaxy at the top spot. Beyond the 26 ecosystem, people like makeup artist Michelle Phan, webseries host turned New York Times best-seller Hannah Hart, and YouTube star Grace Helbig have all parlayed their internet fame into more or less mainstream success. In April, Handwritten, the debut album from Vine star Shawn Mendes, landed at No. 1 on the Billboard chart.

Valiando Rojas is fond of saying she and DigiTour are “in the business of creating best-day-of-your-life experiences,” and it’s clear that for the girls, the meet and greets — and the photos that come out of them — are a large part of that. “They define themselves by the photos they take on social media,” she says. “It’s making your own aspirational fan art and being a part of it.”

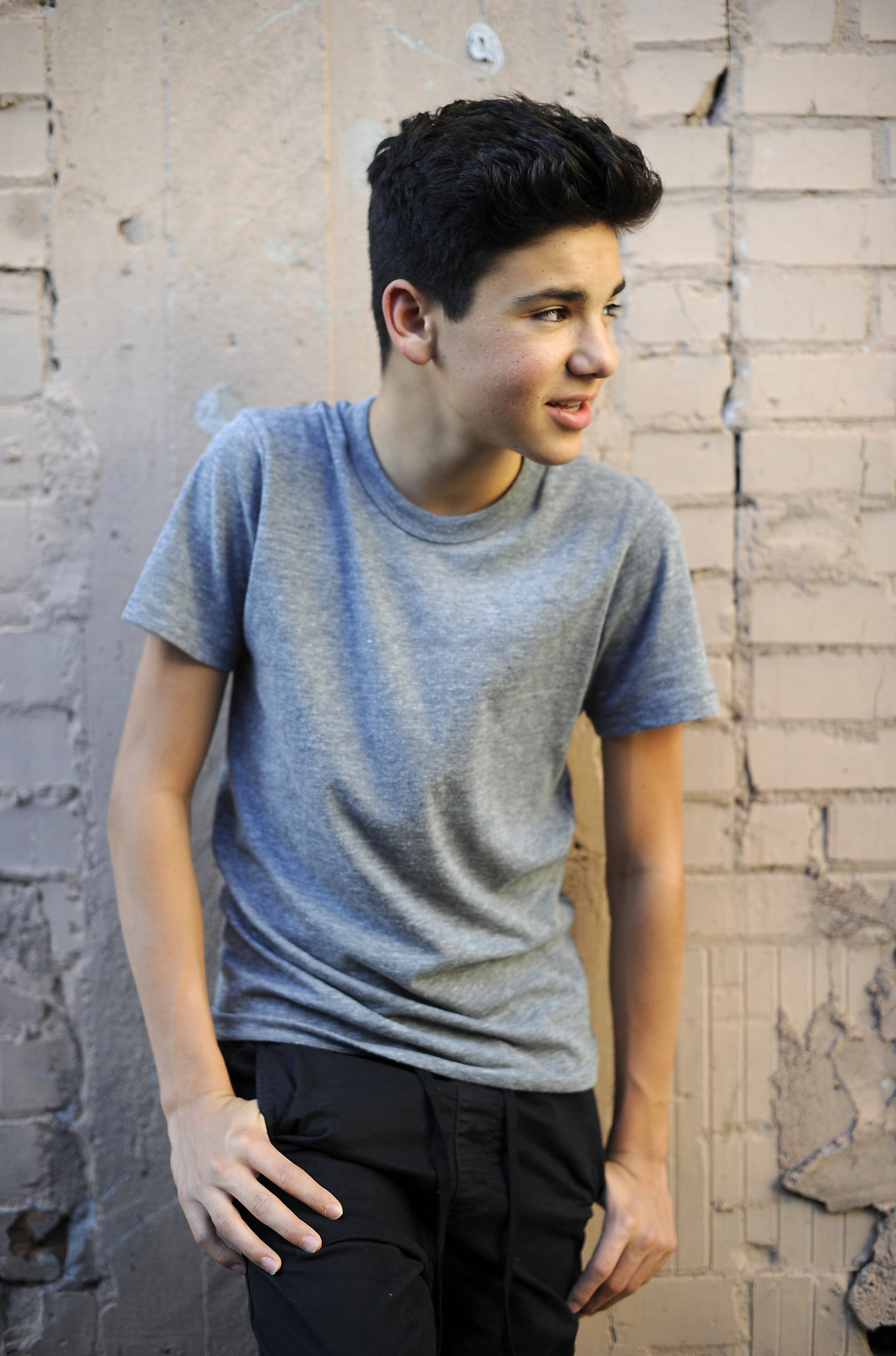

Inside the green room and mercifully away from the heat, Jonah Marais is sitting on the floor, idly scrolling through his phone.

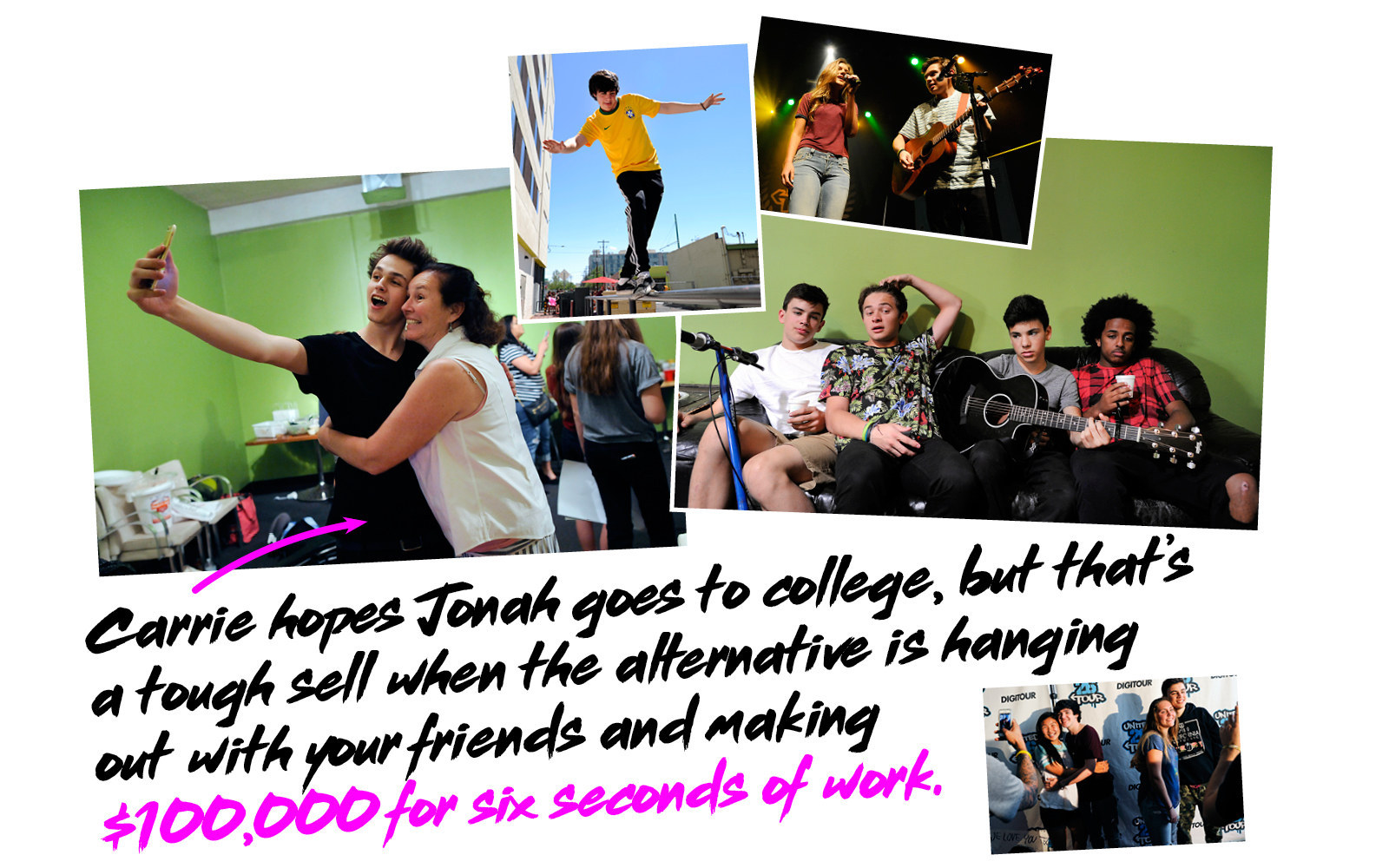

Jonah is a great kid — thoughtful, smart, and clearly very sensitive, with an unconscious habit of placing his hand over his heart in photos and when he’s trying to make a point. His mother, Carrie, is a midwife, and his father, Tim, is a professional musician working in what Carrie describes as “spiritual-focused easy listening.” (Marais is not their real last name, nor is it Jonah’s — after a few too many fans found their address online and showed up at the family home, Jonah’s parents asked that he use a stage name. It’s a reference to a small town on Lake Superior that the family likes to visit.) He grew up in the suburbs of Minneapolis playing travel baseball, attending Waldorf schools, going to church most Sundays, and singing with his family.

Jonah was discovered less than a year ago, at an event not unlike the one that’s currently transpiring outside, when he and his sister drove to the Twin Cities for MagCon (short for “Meet and Greet Convention,” a DigiTour analogue). That’s where he met Cameron Dallas, the Griers, and several other internet celebrities; by virtue of chance or persistence or those cornflower-blue eyes, Chad Grier took an interest in him, signing him to 26. This is his first tour, and the first time he’s been away from his family for more than a week.

Life on tour is full of small indignities — tiny bus bathrooms and tiny bus beds, late dinners, long drives, infrequent showers — but the most crazy-making of all is how sheerly, stupidly impossible it is to be alone. So at first it looks like Jonah is trying to do that — find a sliver of silence and space amid the chaos of the meet and greet. But as it turns out, at this moment he is slumped and silent for the same reason teenage boys have been slumped and silent for centuries: girl problems. He and his girlfriend are going “through some stuff,” and he’s not feeling well: He hasn’t been eating or sleeping, and earlier this afternoon, he threw up, “just from the stress.” This is his first big breakup and he looks absolutely miserable.

Outside, the sun blazes down and the meet-and-greet conveyor belt spins on. The girls who came for Jonah are probably complaining, a thought by which he’s clearly a little tortured. Though he wouldn’t put it this way, it is, after all, his job to smile and say I love you and get fangirl sweat and mascara on his new white shirt — no matter what’s happening, no matter how tired or heartbroken or sick he is. It’s his job to create "best day of your life" experiences. It sounds completely fucking exhausting.

“When you do a meet and greet, every single girl wants something special from you — an extra little hug or something,” Jonah tells me later. “And that takes something out of you, almost — like, emotionally, you know. You have to be so willing — to hug and say ‘I love you’ so much. And you have to talk to every single person individually — which I love doing, but it’s actually, like, really emotionally tiring.”

The advent of social media has created certain expectations for all pop stars, but social media is usually a one-way street: a purportedly tossed-off tweet here, a #nomakeup selfie there. But the kids of DigiTour are actually interacting with fans, and they’re doing it on their own. As a DigiTour employee observed, “Katy Perry doesn’t do this” — or at least not on this scale. When they aren’t sleeping or performing or meeting and greeting, they’re scrolling through the legion of tribute Instagram accounts set up in their honor or DM'ing lucky fans on Twitter. When so much of your fame is predicated on the fans feeling like they know you, you have to keep it that way — even as the number of fans balloons. And when your job is to be yourself, there’s a way in which you’re always working.

It’s telling that DigiTour’s fans almost exclusively describe their relationships with the boys in transactional, two-way terms — in their vernacular, they don’t admire them; they “support” them. They haven’t been watching their videos and ogling their pictures for weeks or months or years; they’ve “known” them for that long. Because the boys still have relatively small fanbases — even a Grier brother is nothing compared to, say, Taylor Swift or Drake — there’s a certain sense of ownership to the fandom: The girls feel responsible for the fame, and the famous feel beholden to the girls. As one fan in Vegas, a bubbly 13-year-old wearing shorts with the word H<3YES printed across the rump, explains, “It’s like they’re your friends. Even though they’re not there physically, you know them from Twitter.”

All that intimacy means hundreds, sometimes thousands of strangers confiding in you — often about very heavy subjects. “Some of the girls will say stuff like, ‘Because of you, I’m clean for 30 or 60 days,'” Carrie tells me. “Or ‘I haven’t cut anymore.’ And as a 16-year-old, I don’t want him to feel all that pressure.” At Carrie’s behest, Jonah started tweeting out a suicide hotline number periodically. “You can’t take it on that you’re responsible for somebody else’s well-being, but you can be positive and bring them up.”

A few weeks after the tour, I speak to Deja, a 14-year-old Jonah obsessive from suburban Oregon. This spring, she sent Jonah a “long note” — actually a series of Twitter direct messages — about some issues she’d been dealing with. “I was going through a really hard time,” she explains. “There was some stuff with my family, and my parents were going through some stuff, and — I’m living with my grandmother right now. And I was feeling like my family would never be back together again. And, um, I kind of just didn’t want to live anymore. So I sent him this note, and he actually responded, saying to stay strong and stuff. He saved my life.” Deja’s grandmother bought her a meet-and-greet ticket to the Eugene show so she could talk to Jonah in person. “He smiled at me and it made me so happy.”

If the thought of having complete strangers’ mental health in his hands at the age of 16 — not to mention the prospect of heading into the packed, sweaty auditorium mere hours after losing his lunch in the green room’s tiny bathroom — is daunting to Jonah, he does a pretty good job of hiding it. “This is what I wanted,” he says, straightening himself a little against the wall. “This is the goal. Like, yeah, it’s hard work, but it’s paying off. I’m seeing the increase on social media and the overall interest in me. It feels really good to see that.”

Jonah and I sit there for a while on the floor. At some point, I ask him why he’s telling me — a near stranger, a reporter, an adult — all this stuff.

“Um, I mean. Well. I don’t go to high school. So I don’t really have that many friends.”

All the kids have left school, either permanently or in a way that’s notionally temporary but seems, in all likelihood, to be permanent. Most are taking online classes toward their GEDs. Some, like Alyssa, already have their high school diplomas. It’s better this way, they say.

“I definitely miss the social aspect of it, and my friends and stuff,” says Jonah. “But at the same time, the other kids don't really get what I'm doing.” He and most of the other guys on tour make some kind of reference, usually veiled, to people at school — especially other boys — giving them a hard time. After all, if escaping ostracism in high school is about being as invisible as possible, as much as possible, they don’t have that option. It’s hard to stay in touch when leaks force you to change your cell phone number once every six months, or when you can’t go to a mall or a high school football game without being mobbed, or when a tour takes you away from home for weeks at a time.

Alyssa is barely in contact with her friends from high school. “I didn't have that many,” she says. “I had one very close hometown friend, but she got upset because I was too busy.” She explains this more or less dispassionately, but she also admits that life on the road can be isolating — especially as the only girl and the tour’s oldest member.

"I help them with advice because I am older and a lot of them are younger. They have, like, confidence issues and things like that. A thing that’s weird is that I’m literally never around people my own age. It’s always older or younger. Isn’t that weird?”

The L.A. show is, as Tez will later say, “hype.” The crowd is even bigger and more enthusiastic than it had been in San Francisco, so much so that fully a dozen girls are escorted out of the venue, crying and hyperventilating. Jonah drinks some water and absentmindedly chokes down a tuna sandwich and ultimately makes it onstage, apologizing for missing the meet and greet before launching into his bit, a mashup of Drake’s “Hold On, We’re Going Home,” Biz Markie’s “Just a Friend,” and Mendes’ “Life of the Party.”

Because this is L.A., where many young internet stars move as soon as their celebrities and paychecks warrant it, about a dozen other social media celebrities come out to show their support. Nash Grier and Cameron Dallas are here, and so are Jack and Jack; Madison Beer, a singer and Bieber protégé; Mahogany “Lox” Gordy, another singer; Maddie Ziegler, of Dance Moms and the video for Sia’s “Chandelier”; and Bryant Eslava, who wears a straw fedora and introduces himself as an “Instagram photographer.” During the show, most of them gather on a balcony overlooking the stage, taking pictures and chatting; when they tromp down the stairs to join the rest of the teens onstage for the finale, the venue goes electric.

After the show, they all gather in the green room. At another kind of after-party for another kind of show, it wouldn’t be long before someone pulled out a six-pack or a joint or a mirror and a credit card. But here, the vice of choice is Red Bull, the most popular activity is skateboard tricks, and the entertainment is Top 40 hip-hop pumped out of tinny MacBook speakers. It’s kind of nice.

Tucson, April 30

Today is a day off, which mostly means napping, laundry, proper showers, and yet more skateboard tricks, this time outside the hotel at which we’re all staying overnight. But it also means work. Up on the sixth floor, Jonah opens his laptop and boots up YouNow, the live-streaming platform on which he has about 65,000 fans. It’s a simple product — pretty much just a video feed with a scroll of live comments — and Jonah’s performance, if you can call it that, mostly consists of a stream-of-consciousness monologue. But it’s easy to see the appeal: It feels a little bit like FaceTiming with a long-distance boyfriend. And today, Jonah is especially emotive. “It’s been a little rough,” he says, casting his eyes downward. He pauses for a long beat and then draws in a breath before looking back up at the camera. “But even when I’m upset, I know I have you guys.”

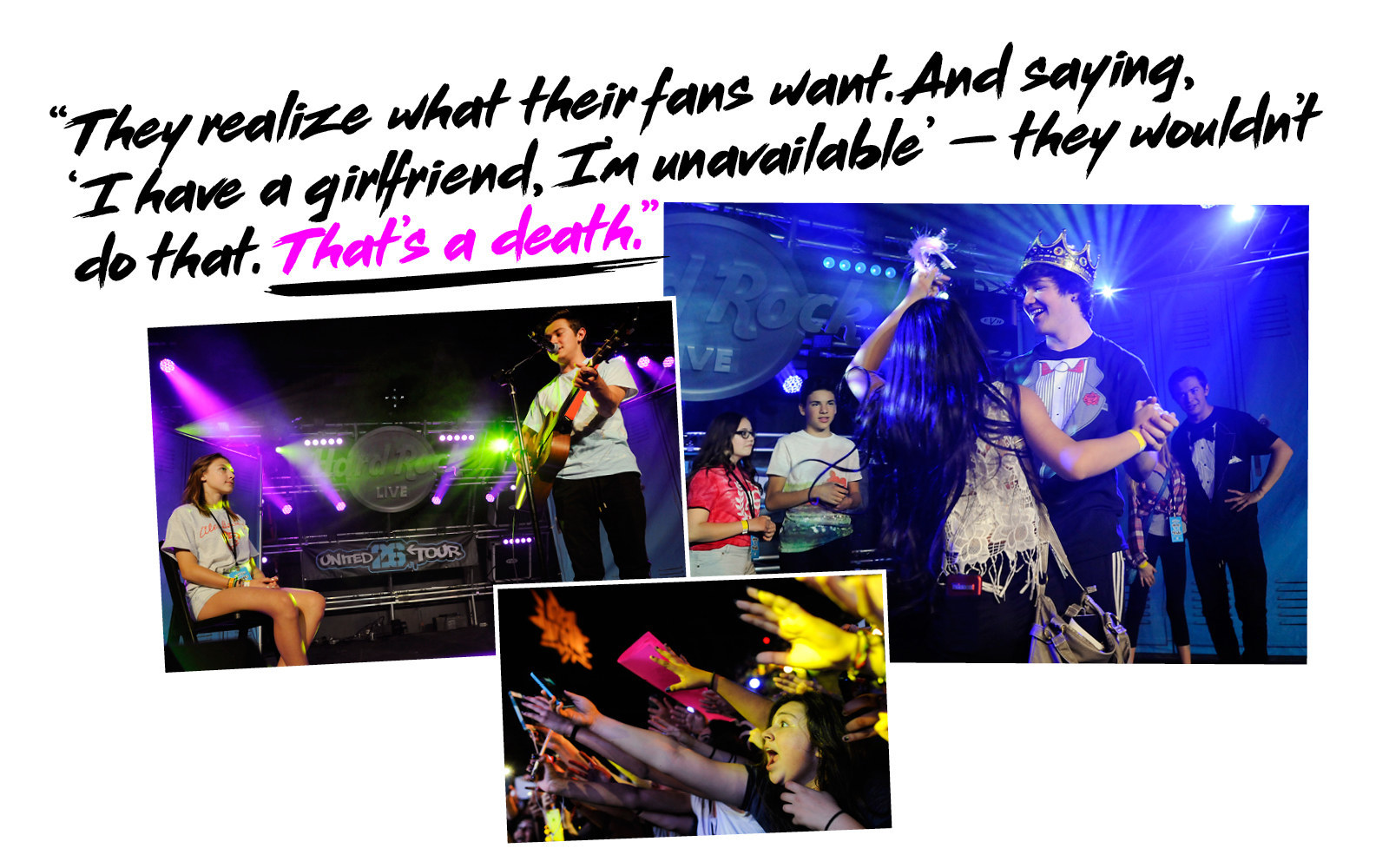

Jonah never exactly names what’s going on with him, likely for the simple reason that for him and the rest of the boys, being perceived as taken would be very, very bad for business. See enough of these shows and it becomes clear that each of the girls who shells out for the meet and greet or waits in line for hours hopes, in some giddy, secret part of her brain, that Hayes or Aaron or Tez will meet and fall in love with her — and that Hayes and Aaron and Tez know this too.

This is why the meet and greets are so lucrative, and why the whole enterprise is structured around a deeply, almost cartoonishly romantic display of grown-up courtship, or at least that which can be believably performed by teenagers: fake proms attended by kids who have never and will never go to an actual prom, hundreds of “I love yous” whispered between people who are likely too young to have said and meant the real thing, a roomful of prepubescent girls imploring a boy to “TAKE IT OFF! TAKE IT OFF!” seemingly more out of habit or performance or obligation than genuine sexual desire — a Xerox of a Xerox of adult romance. There's a reason girls love this type of star, and it's because at 8 or 12 or 15, sex is still, frankly, scary: They want the swoony stomach drop of meeting an idol close up — not an actual sexual encounter with said idol.

Which is probably why DigiTour is, crucially, still very chaste: Valiando Rojas says she aspires to a “PG-13 atmosphere,” and, by and large, she succeeds. Though the mind races at the prospect of what a good-looking 16-year-old boy might be inclined to do with millions of adoring girls wrapped around his finger, if anything untoward happens on the bus or backstage, I didn’t see it. Even the segment of the show devoted to a cast round of “Never Have I Ever” — usually played as a drinking game; almost definitionally a way for teenagers to brag about their sexual exploits — becomes, in the DigiTour context, sweetly tame, the kids offering up experiences like cow-tipping or skiing. Onstage and off, the boys are wholesome, athletic, polite, presumably straight (though I didn't explicitly ask), outwardly middle-class, and, with the exception of Tez, white — custom-built to be at once broadly irresistible to teenage girls and nonthreatening to their parents. And being everyone’s imaginary boyfriend simply does not square with being anyone’s real boyfriend.

“They’re definitely fuel for this fantasy machine,” Valiando Rojas tells me when I ask her whether DigiTour advises the teens to keep their relationship statuses quiet. She says they do not — and Spiegel makes the same claim about 26 — but she also implies that the boys are savvy enough on their own to know what’s good for their brand and what isn’t. “Even if they’re not super aware of it in an intellectual capacity, they know that girls want to marry them,” Valiando Rojas continues. “And, obviously, they can’t marry 20,000 girls. They realize what their fans want. And saying, ‘I have a girlfriend, I’m unavailable’ — they wouldn’t do that. That’s a death.”

Relationships aside, the fantasy machine breaks down sometimes. It did in June, when a video surfaced of Carter Reynolds, another Vine star (and former 26 client) apparently pressuring his underage then-girlfriend into oral sex. It did in March, when Cameron Dallas was busted for vandalism. And it definitely did last summer, when Nash released a Vine in which he implied that “fags” were responsible for the spread of HIV; the internet erupted. Any celebrity will land in hot water sooner or later, and any teenage boy will say or do something stupid if you watch him long enough. But the very qualities that make this type of celebrity — unvarnished, intimate, organic — compelling are also the ones that make it much more impervious to control or management.

“Social media today has the ability for people to expose their entire life,” Spiegel says when I ask him about this tension. “These guys put everything out there — their lives, their thoughts, their Snapchat stories. That’s why these kids really relate to the teen demographic. And when they go through a hard time, and regain themselves and explain it, that’s better than some PR firm doing it for them.” When I point out that Nash Grier’s homophobic rant wasn’t exactly a standard-issue adolescent “hard time,” Spiegel says, “He was being a 15-year-old kid who was being naive and looking for some engagement on Vine. There’s definitely going to be some mistakes.”

At any rate, in Jonah’s case, all the caginess makes for a short YouNow broadcast. He talks to the camera for a few minutes before ending the session. But first: a phone call to a fan, dialed, as usual, from a blocked cell phone number and shown, of course, onscreen. “Bye, I love you,” he tells his lucky interlocutor at the end of the call.

Ten minutes later, he sidles up for a late lunch at the bar, one of those neon-lit, conspicuously trendy things that looks grotesque in daylight and is favored by mid-rate hotels everywhere. It’s about 4 p.m. and this will be his first meal of the day. He orders a Caesar salad and wedges himself onto a stool between a pair of sisters visiting from Wisconsin and an elevator repairman from Phoenix. None of them have any idea who he is. Jonah makes easy small talk and minor headway on the salad before noticing the group of people standing in the lobby. It’s a mother, her 15-year-old daughter, the daughter’s friend, and a very bored-looking younger brother; the daughter figured out where the boys were staying via some complicated-sounding Snapchat sleuthing and begged her mom to drive to the hotel.

The social media celebrity machine is dependent on a carefully calibrated mixture of giving and withholding: Invite six girls onstage for the prom sequence, but not more than that. Follow a handful of fans back on Twitter, but not all of them. It’s a precarious balance that can quite easily get out of control — especially without any of the protections or layers of access afforded by major, pop-star-style celebrity. Jonah excuses himself and ambles to the elevator, politely avoiding the girls. He leaves his salad mostly unfinished.

Tucson, May 1

“I want to do, like, everything,” says Tez when I ask him what he hopes for his future over a bowl of Fruity Pebbles in the Rialto Theatre’s green room. “I'll do radio, host TV, you know what I'm saying? Even short films, regular films, do a little music here and there, like, just try everything.”

“I definitely want to have a career in music,” says Jonah when I ask him the same question. “I want to be taken seriously as a musician. It's hard to be taken seriously by anybody above the age of 18 or 20 or something when you're doing a social media tour. Of course, it's serious that we're selling as many tickets as we are and that we're gaining as much of a kind of momentum as we are, but ... to really be taken seriously as a musician I feel like you have to really release original music and put yourself out there more as an artist. Does that make sense?”

Of course it does. DigiTour may be a high-profile showcase for these kids’ musical talents, but the fans are coming for the meet and greet and the eye candy, not the artistry. And even though it’s not all that hard to imagine a future in which social media tours will be a widely understood precursor to broad success, we’re not necessarily there yet. For every Shawn Mendes or Cameron Dallas, there are dozens — hundreds? thousands? — who will not break through to the mainstream. It’s hard not to wonder what’s next for people like Jonah and Aaron and Tez: After all, it’s one thing to be 16 and cute, but quite another to be 26 or 36 and...not. Jonah's mom tells me she hopes he goes to college, but that’s a tough sell when the potential alternative is hanging out in L.A. with your friends and making $100,000 for six seconds of work.

And, there’s this: Fame is irreversible. There is no unfamous; there’s just formerly famous and washed-up and the confused stares of people who recognize you from somewhere but just can't quite place it. As new and as niche and as not-quite-the-Grammys their celebrity is, it is, unequivocally, some kind of celebrity, and the kids of DigiTour will never know how it feels to be really, truly anonymous. This is true of all teenage celebrities, of course, but the old model for fame presented more roadblocks, more bottlenecks, more moments for self-reflection and stock-taking. It may seem like, say, Ariana Grande became famous overnight, but really, she’s been meeting with agents and strenuously crafting an image for years. For people like, for example, Jonah, it’s possible to quite literally wake up one morning with tens of thousands of followers — by yourself, as yourself, without engaging with much of the typical celebrity infrastructure at all, and without necessarily taking the time to consider the life-altering weight of such a choice.

Not that they’re too concerned. “So, say you won the lottery,” Hayes says. “Oh no, that's a bad analogy, that's a bad analogy. Say you're working toward something and you achieve that goal. You’re not just gonna cut it off, right? You’re gonna keep progressing at it. Keep building it up.” Besides: He’s really, really young. “I’m sure if you ask Hayes about his future, he’ll say, ‘I’m 14. I want to ride dirt bikes,’” says Valiando Rojas.

“Honestly,” says Hayes when I ask him, “if I could choose something, I would go be a professional dirt bike racer. And I’m giving music a shot — see if that's something I want to pursue. If not, then, um, I guess being an actor maybe. I don't know.”

Carrie has flown in from the Twin Cities to see Jonah; she arrives just before the show, rolling suitcase in hand. “It felt like now is the time to check in with him,” she explains. “See how he's doing. Be a mom.” She glances over at him, sitting on the couch. “I think he needs me.” During the meet and greet, I watch her do a little wiggle in place to the strains of Pharrell’s “Happy” as she struggles with the fans’ cameras. During the show, she watches from the pit, along with all the other moms. She’s smiling the whole time.

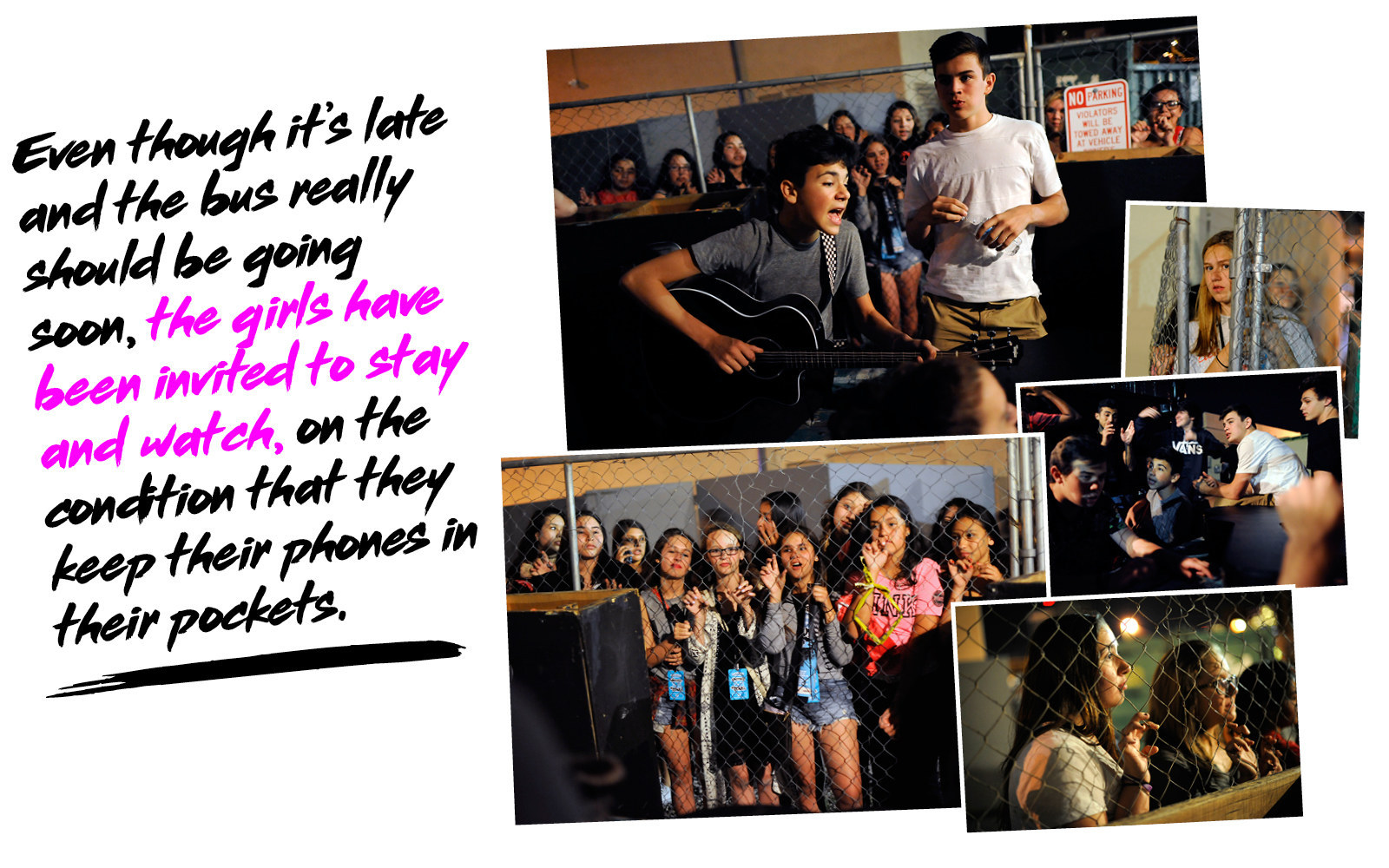

After the show, the kids gather at a picnic table outside the venue — at first just to talk and eat dinner and wait for the crew to pack up, but then Daniel lugs out his guitar and begins to play. About two dozen fans have, as was inevitable, found them, and even though it’s late and the bus really should be going soon, the girls have been invited to stay and watch, on the condition that they keep their phones in their pockets. So they stand on the other side of a chain-link fence, arms wrapped around each other's waists, tears streaming down their faces. Carrie is here, and so is the crew: Tom, the lovably surly middle-aged Irishman who’s toured with U2 and Bruce Springsteen; Griffin, Hayes’ twentysomething handler; Troy, who recently dropped out of Harvard for the opportunity to travel the country begging young girls not to jump on top of other humans, and who seems to absolutely love his job. And they all — we all — begin to sing.

This is the first time I have seen seven kids organically and sustainedly gathered in the same place at the same time, and they actually have some chemistry. They run through Ed Sheeran’s “Thinking Out Loud,” then Sean Kingston’s “Beautiful Girls,” then Miley Cyrus’ “We Can’t Stop.” “Do ‘Night Changes,’” a fan asks, and so they do "Night Changes," someone in the darkness shaking a set of keys along to One Direction's chorus: “We’re only getting older, baby / And I’ve been thinking about you lately / Does it ever drive you crazy / Just how fast the night / Cha-aa-nges.” The vibe is something between a folk band jam session and a summer camp sing-along. They are a pop-up boy band minus the band. After this, they’ll scatter — Hayes back to dirt bikes and North Carolina; Jonah to the poetry festival he and his family have been going to every summer for years; Aaron, he hopes, to Los Angeles. But right now, the moon is full, and the girls are wet-cheeked and silent and positively beaming through their tears, and suddenly Valiando Rojas’ line about best-day-of-your-life experiences feels like something more than a line.

“I feel so happy,” one of the girls, a reedy blonde with pink braces, whispers to a friend, still staring at the boys from the other side of the fence. “It’s like we’re just hanging out with the people we like. Just being around them makes me happy.”

Las Vegas, May 2

Tonight happens to be the night of the big Floyd Mayweather–Manny Pacquiao fight, and so the scene on the Vegas strip is even weirder than usual, the street clotted with revelers wearing too-big T-shirts and clutching massive drinks. Three floors up, in the Hard Rock Hotel’s massive performance space, the meet-and-greet engine revs up again, hundreds of girls patiently snaking a line around the bar. It’s just before 1 p.m. and bright sunlight is streaming in unrelentingly through big windows. After this show, the Hard Rock will host a local high school’s actual prom, a fact that reminds Tez that in a parallel universe, back home in North Carolina, this would be his prom night too. After that, the rapper Flo Rida will host a fight after-party, and the boys will get back on the bus and head to Phoenix, then to San Antonio and Austin and New Orleans and six other cities before, finally, home.

But right now, in the green room, they are killing time. Aaron vigorously douses himself in cologne. Jonah FaceTimes with his father and his older brother, him mom eagerly peering over his shoulder. Alyssa is prostrate on a couch, covered in blankets; she still hasn't fully shaken whatever bug she caught in San Francisco. The remaining four sit next to each other on another couch, each watching a different video on their phone.

Everywhere the septet goes becomes theirs very quickly, every surface littered with the ephemera of teen life, and here in Vegas, entropy has set in even faster than usual. Plastic, condensation-clouded clamshells of food rest on couches and chairs and tables and floors. A bottle of ketchup sits under a chair. There are MacBooks everywhere. The green room bears artifacts of others who’ve come through it before, on tours at once exactly like and nothing like this one: a framed picture of the Beatles on one wall; on another, Ray Davies’ guitar, encased in glass. A few girls have found the green room and are passing notes with their phone numbers and Twitter handles under the door.

And then, soon enough, it’s time to go out to the meet and greet — you can hear the shuffling of thousands of feet, the indistinct, aggregated chatter of thousands of girls. Hayes finishes his burger in a single bite and rises to meet them.