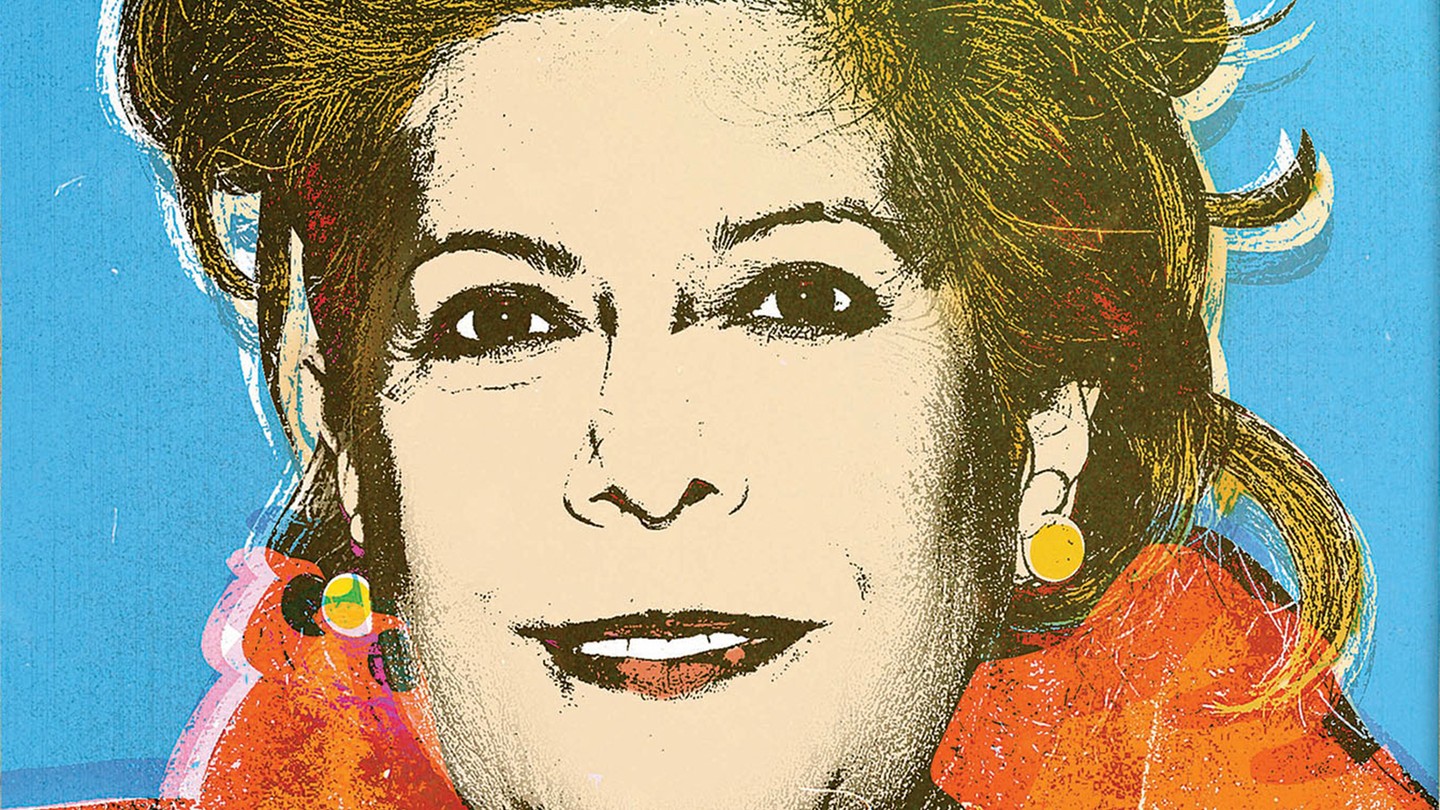

The Mysterious Columba Bush

Who is Jeb’s wife, what effect will she have on his campaign—and what effect will his campaign have on their marriage?

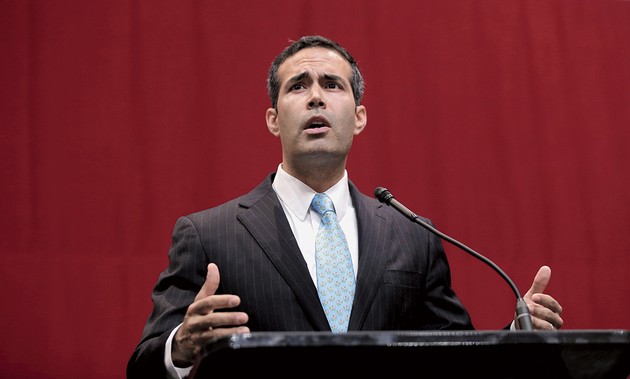

Now and then in an otherwise unmemorable speech, Jeb Bush will drop a mention of his wife, like a sudden pop of color. At an event in Nevada this March, one of his first speeches of this campaign season, before a crowd of what The Washington Post called “everyday Americans,” Bush opened with a husband-still-in-thrall routine. His life, he said, can be divided into two parts: “b.c. and a.c.—before Columba and after Columba,” referring to Columba Garnica de Gallo, the woman he fell madly in love with while on a high-school trip to Mexico and then married 41 years ago.

The crowd, full of seniors and some Spanish speakers, awwwed and cheered. Columba herself was not in attendance. Perhaps because he hadn’t officially declared his candidacy for the Republican presidential nomination, she felt no hurry to claim her title as candidate’s wife.

Friends of the Bush family to this day tell stories of Jeb and Columba’s deep and obvious affection for each other. And yet by any straightforward measure of compatibility—family background, interests, personality, ideas about a pleasant way to spend an afternoon—they seem to have very little in common. Take, for example, her husband’s lifelong career passion and the main preoccupation of his family for at least three generations. In 2001, after she’d been the first lady of Florida for two years, a reporter asked whether she and her husband talked about state policy. “Never,” she answered. “We talk about our daughter and sons, and cats and dogs and silly things.”

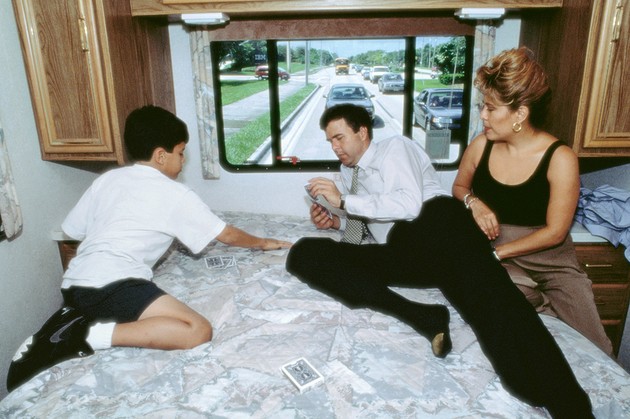

The role of political spouse always entails sacrifice, but Columba’s case has been extreme. Jeb’s time in office coincided with stretches when Columba was reportedly unhappy, because of his absence or because of troubles with one of their three children or because she herself had landed in the news in ways that mortified her. It was during Jeb Bush’s governing years that Columba let it slip to the press how her husband’s career had damaged their children, and that she reportedly told Jeb he had ruined her life. During his governorship, which ran from 1999 to 2007, she often retreated to Miami while he was living in Tallahassee.

All of which makes you wonder what it will be like for her to live through a national campaign and possibly a presidency, during which the mode she’s enjoyed least will become her entire existence. In the Jackie Kennedy years, she might have gotten away with a smile, a few supporting speeches, and an appropriate cause or two. (One of the rare YouTube videos of Columba shows her giving a Jackie-like tour of her house to a Spanish-speaking TV anchor.) But feminist resistance to the idea of wife as silent prop has in some ways put more pressure on a first lady to be serious and weighty and comfortable in front of the camera, giving someone like Columba no easy place to hide.

Despite her in-laws’ history, and despite eight years of being the first lady of Florida, Columba has consistently talked about politics as if it’s something that faraway, alien people do. When, in 1992, a reporter from The Miami Herald asked her whether she was enjoying her father-in-law’s presidential campaign, she said, “I want to go back to my kitchen, to do the homework with my kids, and—why not—to watch television.”

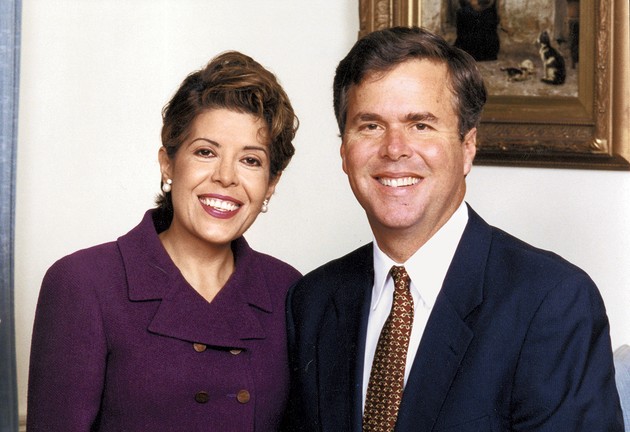

“She had the most limited role of any spouse I’ve ever worked with,” a strategist on Jeb’s 2002 reelection campaign told me. Columba would participate in events now and again, but everyone understood that a public role “was not in her comfort zone.” Her influence was felt on the campaign mostly because members of the staff knew that they often had to make sure Jeb ended his days early enough to be home for dinner. Those who know her well paint her as the anti–Claire Underwood, the political spouse on House of Cards. You could also describe her as the anti–Bill Clinton, her possible counterpart in next year’s general election. “She is not somebody who is reading any political reporting or interested in being in the room to strategize tactics. She is completely uninterested in that,” says Jim Towey, a friend of the couple’s who served in George W. Bush’s administration. “In politics you get a lot of clone people. And she is so not the clone.”

Who she is is a harder question, due in part to her reluctance to develop a public persona or talk to the press. (She wouldn’t talk to me, even with campaign season heating up, although Jeb and I corresponded.) Bush loyalists bristle at the idea that Columba would have trouble fitting into the role of first lady in the White House. One scolded me that the press was just being “stupid” and “lazy” by saying that she hates public life and failing to recognize all the causes she has taken up over the past 15 or so years.

It’s true that she has adopted first-lady-worthy causes, working with the Florida Coalition Against Domestic Violence, the Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse, and Arts for Life, a group that gives scholarships to young artists. By all accounts, she advocates earnestly and effectively, visiting shelters, studying reports on addiction in adolescence, putting together exhibitions, and connecting donors with charities. Everyone I interviewed who’s worked with her says she doesn’t seek the limelight, nor even any recognition for her actions—which is admirable. It’s admirable, too, that she’s been able to remain, well, normal, despite her marriage into such a high-powered political clan. But as a modern first lady, she’ll be expected to come out from behind the scenes. And whether she likes it or not, what she does and how she feels will affect her husband as a person and as a candidate—and that interplay will be endlessly dissected.

These days, Columba’s distaste for public life, historically a source of volatility for Jeb, is being reframed as a balm. “What he loves about Columba is that she’s an emotional anchor for him,” Ana Navarro, a family friend and a Republican strategist, told me. “She lives outside the political bubble and brings his focus back to the really important things in life, like family and friends and faith.”

“Everyone seeks emotional refuge,” Al Cardenas, another family friend and a former head of the Florida Republican Party, told me. “And that’s what she provides. She brings sanity into a world filled with politics.” But even Cardenas seemed to sense that it can be hard to conceive of them as a couple, like Bill and Hillary or Brad and Angelina, because she’s so absent from the publicly visible parts of Jeb’s world. So at the end of our conversation, he felt the need to make it explicit to me, about Jeb’s wife of 41 years: “Look, he loves her unconditionally. She is a major, integral part of his life.””

Jeb Bush’s courting of Columba at 17 is possibly the most outlandish thing he’s ever done. In a family where the sons traditionally choose their wives from a small society circle, Jeb’s choice registered as baffling, even reckless. In 1970, as a senior at Phillips Academy, a boarding school in Andover, Massachusetts, he took a class called Man and Society, which explored poverty, conflicts, and the dynamics of power. At the end of the winter term, the students could choose to spend three months either in a poor neighborhood in South Boston or in a poor indigenous village outside León, Mexico. Jeb was from Texas and already studying Spanish. Along with 10 other classmates, he opted to skip the Boston winter.

“We actually built a schoolhouse,” Jeb’s former classmate Lawry Bump told me. All these years later, Bump still thinks about the trip sometimes, because it was a “real awakening.” They worked every day to complete the structure; Jeb was quoted in the student paper saying that one of the villagers cried with appreciation. In the late afternoons, the students would all meet up in the main plaza in León and eat—bacon and pancakes for the equivalent of 40 cents—and then in the evenings they’d sometimes get together at one of the houses where they were staying to drink and play poker.

As Jeb tells the story, one day he saw 16-year-old Columba across the plaza and it was love at first sight. “Lightning” is how he put it to The Boston Globe. She was not a society girl from Mexico City. Even by the standards of small-town León, she was on the social fringe. Relatives have described her as a free-spirit daughter of a divorced mother in a community where, in her own words, divorce was a sin.

Not that it matters much now, but Bump’s version of the couple’s meeting is a little different. He says that another classmate, John Schmitz, had met Columba’s older sister, Lucila. Schmitz needed a wingman for a double date and called Bump. “As much as I would have loved to have been set up with a girl down there, I literally had about a 104-degree fever and was down with Montezuma’s revenge,” Bump told me. “The next move for John was to get with Jeb.” (“I don’t know if he would have met Columba on his own,” Al Cardenas says. “You know, Jeb’s more of an introvert. He’s not the type to go up to an unknown girl and say, ‘Hi. I’m Jeb Bush. Let’s have a cup of coffee.’ ”)

I asked Jeb by e-mail about their first encounters, because lightning seemed like a word out of a romance novel and not quite real. Here is how he elaborated:

I fell in love at first sight with my wife. I can’t explain it but it was transformative. She was and is a beautiful woman. That was and is part of my love of her for sure. She played hard to get which made me more driven to get her. She was different than me which drew me to her. She had great instinctive insights into life that I really appreciated. Thank God I met her and thank God she let me into her life!

For the last month of their field trip, the other Phillips Academy kids did not see much of John and Jeb. Those two spent their time double-dating, driving around in Lucila’s car. From the start, Jeb told his classmates that he was in love. At the end of the trip, he told them all he was not going home with them; instead he was taking Columba on a trip to Acapulco.

To Jeb’s friends, it looked like meeting Columba allowed Jeb to settle into who he actually was. Before that Mexico trip, Jeb had been known in school as a good tennis player, an indifferent student, a bit of a bully, and a toker, a guy whose room you could go to in order to get high. “I was a cynical little turd at a cynical school,” he once said.

Yet by the time Jeb returned to Andover, he had matured. He made the honor roll for the first time and shared a prize for a history paper. “He just wasn’t messing around as much with drugs and alcohol,” Bump recalled. “Everyone knew he had changed. We figured he was just devoted to her.” The partying and restlessness that characterized his older brother, George W., into his 40s, Jeb got out of his system before he turned 18.

He graduated from college in two and a half years, “thanks to a newfound focus,” he once said. During the holidays in 1973, he proposed to Columba, in Spanish, at a Mexico City restaurant. She took a day to answer, then gave him a peace-symbol ring. When he called his parents, George and Barbara, and told them he was going to marry Columba, that was also lightning—the news hit like a bolt “from a West Texas thunderstorm,” write Peter and Rochelle Schweizer in their 2004 book, The Bushes: Portrait of a Dynasty. Jeb did not introduce Columba to his father until a small dinner right before the wedding. “How I worry about Jeb and Columba,” Barbara wrote in her diary. “Does she love him?” The wedding took place at the Catholic student center at the University of Texas at Austin. Columba spoke no English, so parts of the service were conducted in Spanish. “Colu’s entry into the Bush family would prove difficult, a process that even after thirty years is still a work in progress,” the Schweizers write in their book. “At family gatherings the family would laugh, play, and tell stories. Colu would just sit, smile, and wonder.”

“Nobody really knows Columba,” Towey told me in February. “She is very private, and on many levels, her life is wrapped in mystery.”

Various ideas about her have grown to fill that void. She likes making “huevos rancheros for breakfast” and “for a real treat” hires a mariachi band to play for her friends. She enjoys “simple Latin fare like jamón serrano at no-frills restaurants.” She would “trade 20 society galas” for one juicy telenovela in the comfort of her home. This is the ethnic flavor that has been mixed and remixed into many profiles over the years, typically written from afar. (These quotes are from the Chicago Tribune, The New York Times, and The Washington Post, respectively.) Compare this with what was said about Judith Steinberg, Howard Dean’s wife and the last presidential contender’s spouse who had little interest in political life and rarely talked to the press. She, too, was often described as shy. But because she was a Princeton-educated Jewish doctor, the color that filled the blank around her was different: “smartest girl in med school”; “I-don’t-know-how-she-does-it working mom”; “blithely uncoiffed, unadorned, unstyled.”

Friends of the Bush family tend to describe Columba in mystical or artistic terms. “Jeb just soldiers on, man. He’s always on fast-forward,” Towey, now the president of Ave Maria University, in Florida, told me. “But Columba, she ponders. She’s much more introspective, much more about the unseen world.” In 2003, Towey and Columba were part of a delegation to Rome to celebrate John Paul II’s 25th anniversary as pope. The group was moving through Saint Peter’s Basilica, in Vatican City, when someone noticed that Columba was missing. Towey went to look for her and found her kneeling at a side altar, quietly praying, and that image has stuck with him. “That’s Columba. Anyone that says ‘I know her’? They don’t.”

Or maybe that’s just hagiographic nonsense. Romero Britto, a Miami artist and a good friend of Columba’s, says it’s nonsense. “It’s like, one day you’re a private citizen, and then suddenly you are a public figure and everyone wants to know more about you. She’s not mysterious. She’s just a normal person who loves her family and does the things she likes.”

A New York Times story in February described Columba as an artist, noting that she had just painted a picture of a cat. Britto says she does not paint cats, although he does. She’s an avid supporter of the arts, not an artist—though she has said she wanted to be an artist when she was younger.

If Bill Clinton could be called the first black president, Jeb Bush could conceivably qualify as the first Hispanic one. (The Times recently reported that he once checked the “Hispanic” box on a voter-registration form. Twitter jeered.) Despite the family lineage, the Bushes like to “keep alive the myth of the self-made man,” says Doug Wead, who served as an adviser to both Presidents Bush. “As they see it, what’s important is not blood, not what you were born into. It’s what you did on your own.” Each son has had to at least pretend to strike out on his own, to forge a new identity. Prescott Bush left Ohio for Connecticut to be a banker and later a senator; his son George H. W. Bush decamped to Texas and the oil business. Jeb followed suit not only by moving to a new state but by adopting a foreign culture upon marrying his wife.

After he graduated college with a degree in Latin American studies, he and Columba moved to Venezuela, where he became a vice president of the Texas Commerce Bank. The couple spoke Spanish at home; their eldest son’s first words were agua, jugo, and aquí (“water,” “juice,” and “here”). In 1979, when Jeb’s father began creating a presidential-campaign network, Jeb and his family moved to Miami to help him out. Miami turned out to be perfect both for the family and for Jeb’s ambitions. The Republican Party there was growing, thanks to Cubans who admired President Reagan and Vice President Bush’s anti-Castro policies. Jeb ran for chairman of Dade County’s Republican Party and won—the first political win for his generation of Bushes.

Twenty years later, Jeb Bush became governor as Florida was changing, enabling him to add Central Americans and Puerto Ricans to his list of constituents and allies. Over time, he became what Ana Navarro calls “pan-Hispanic,” meaning he speaks Spanish fluently with an accent that’s not detectable as Cuban or Nicaraguan or Mexican, and has an understanding of each specific culture’s idiosyncrasies. Jorge L. Arrizurieta, a Miami businessman and a longtime friend of Jeb’s, calls him a gringo aplatanado, by which he means “the most Latino American you will ever meet.” Arrizurieta told me that Jeb “enjoys all these Cuban gestures and phrases with friends.” He’ll tap his elbow when someone’s being cheap—a gesture that signifies caminando con los codos, or “walking on your elbows,” which saves wear and tear on your shoes.

He is “completely bicultural,” says Raquel Rodriguez, a Miami lawyer who met Jeb while volunteering on his dad’s first presidential campaign, in 1980, and later served as his general counsel. The day I called Rodriguez, she’d been reading a story in Politico magazine about how much of an introvert Jeb was. But this didn’t wholly jibe with the Jeb she knew. “I mean, he doesn’t want to lead the conga line or anything. But on the other hand, little old ladies come up to him and hug him and kiss him, and he’ll hug them back. It’s a very Hispanic trait … He gets that we like to invade your personal space.”

In April of last year, Jeb uttered perhaps his most memorable phrase to date. In a speech about immigration, he called crossing the border illegally “an act of love.” He painted a humane and specific portrait of the people who come to the United States illegally: “The dad who loved their children—was worried that their children didn’t have food on the table. And they wanted to make sure their family was intact, and they crossed the border because they had no other means to work to be able to provide for their family. Yes, they broke the law, but it’s not a felony. It’s an act of love. It’s an act of commitment to your family.”

Politico’s Web site later counted those among the words he will most regret, because for so many conservative primary voters, affection for border crossers is a deal breaker. But there’s no doubt that the sentiment behind the words flowed naturally from Jeb’s own teenage act of love.

Columba’s father, Jose Maria Garnica Rodriguez, reportedly crossed the border without proper papers on at least one occasion before he got his resident alien card in 1960. After that he went back and forth between Mexico and America, contributing to Columba’s complicated relationship with him and with the United States.

In a 2004 biography of Columba written in Spanish by Beatriz Parga, whose title translates to Columba Bush: The Cinderella of the White House, Parga writes that her father caused the most painful memories of her life. She says Columba’s father once hit her mother with a belt buckle, breaking her fingers. Her parents divorced in 1963, when she was 10, and many press accounts have given the impression that she never saw her father after that. But Parga’s book tells another story, recounting a trip Columba took to California in 1973 to visit her father. One day he came home from work and discovered that she’d been smoking a cigarette, so he took off his belt and ran after her. She locked herself in a bathroom, and when he left, she snuck off to the bus station and went back to Mexico. Her father’s second wife has told reporters still another version that makes her husband, who died in 2013, look better: she says Columba told her father she was going out to get the mail and disappeared, and they assumed she was going to see Jeb.

However she left things with her father, Columba has made about as vast a journey as any American immigrant ever could, from a barely-middle-class girl raised by a divorced single mother in León, to potential first lady of an American presidential franchise. Yet today, Columba is no more a part of Jeb Bush’s Spanish-speaking political circles than she is of his English-speaking ones. She did not develop a separate life in Miami’s society pages, or become a well-known hostess on the Cuban scene. In fact, as Jeb was smoothly going native, her own cultural transition to Bushland was halting and bumpy. She became an American citizen, in 1979, just so she could vote for her father-in-law for president. “It was a difficult decision to make,” she later told a local paper.

In 1994, Jeb ran for governor against Lawton Chiles and lost. He campaigned six days a week, morning and night, only slowing down when he was “dog sick,” he said. His wife, meanwhile, was home and overwhelmed with raising teenage children. One of them had a drug problem—only years later did they publicly admit that it was their daughter, Noelle. George P., then a Rice University student, was caught by police that year breaking into an ex-girlfriend’s house at 4 a.m. to see her; when her father asked him to leave, he drove his Ford Explorer over her family’s front lawn. The Schweizer biography reports that during that period, several family members overheard Columba say to Jeb, “You’ve ruined my life.”

It’s hard to know how the disappearance of Columba’s father from her life has shaped her relationship with Jeb; perhaps it compounded her anger and alienation during this time. After the campaign, Jeb called the experience the most “humbling” of his life and admitted that it had estranged him from his family. Raised Episcopalian, he converted to Catholicism, partly as a gesture of reconciliation with his wife.

In 1998, Jeb ran for governor again and won. The family relocated to Tallahassee, and as first lady, Columba changed the look of the governor’s mansion. She organized exhibits of the works of Salvador Dalí, Diego Rivera, and Frida Kahlo, and of her favorite local artists. This did not always go over well in a city much further culturally removed from Miami than the 500 miles between them would suggest. “She was doing Latino, not southern belle,” Jim Towey recalled. “And it did ruffle some feathers.” Columba took refuge in the Kool Beanz Café, the rare restaurant in town back then with an adventurous menu, and took walks alone around a Tallahassee park. Eventually, she and Jeb agreed that she’d spend more of her time in Miami.

In 1999, shortly after Jeb won the gubernatorial election, she faced public scrutiny. Returning to the U.S. from a trip to Paris, Columba told customs officials that she’d spent $500 on overseas purchases. She was searched, however, and officials found receipts for $19,000 in clothes and jewelry. A Bush spokesman at the time said she did not want her husband to know how much she had spent. “The embarrassment I felt made me ashamed to face my family and friends,” Columba said at a charity event later that year. “It was the worst feeling I’ve ever had in my life.” She also said, “I did not ask to join a famous family. I simply wanted to marry the man I loved.”

Noelle continued to struggle with addiction during this time. In 2002, at the end of her father’s first term as governor, she tried to use a fake prescription to buy the anti-anxiety drug Xanax, and was ordered to attend a drug-abuse treatment center. Eight months later, while at the center, she was found with a small piece of crack cocaine in her shoe and sentenced to 10 days in jail. A reporter asked Columba whether Noelle’s problems were related to being part of a political family. “Absolutely,” she answered, before stopping herself. In her advocacy, Columba has worked with organizations that highlight the “heartache and destruction” caused by teenage drug addiction. But she keeps her own heartaches private.

In the run-up to Jeb’s prospective presidential campaign, Columba burst back into the news in exactly the way she had dreaded. In February, The Washington Post ran a story about more jewelry purchases. The paper reported that in 2000, less than a year after the customs fiasco, she’d taken out a loan to buy $42,311.70 worth of jewelry in a single day, and that she had spent at least $90,000 at a single South Florida chain store, Mayors Jewelers. This time Columba did not apologize or sound wistful about her fate, and Jeb said nothing. Kristy Campbell, Jeb’s spokeswoman, only confirmed that yes, Columba made jewelry purchases “from time to time,” and left it to the conservative press to call bias on The Post for highlighting a private citizen’s perfectly legal spending habits. The paper used the phrase expensive tastes, which surely had Democratic strategists thinking about Ann Romney’s horse.

What do the jewelry purchases say about the Bushes’ marriage? The Post wrote, “There is no doubt that Jeb and Columba Bush could cover their bills.” But his financial statement for 2000 shows $2.3 million in assets and an income of $202,616, which suggests that a $40,000 purchase was not negligible. It seems especially notable given Jeb’s pride in his frugality, which is, famously, a family trait—Barbara Bush made it clear that the pearls she wore as first lady were fake. Also, jewelry is loaded with relationship significance. Perhaps the Bushes, like many couples, were going through a bad stretch. Or perhaps Columba, despite not being much of a society wife, just has a hard time resisting sparkle. (Old profiles of her mention high heels and Chanel.)

Friends say that Columba’s biggest concern today is keeping Noelle stable and out of the public eye. Now 38, Noelle lives in Orlando, where she works at a software firm. By all accounts, she is okay but fragile. “Everyone’s happy with her progress,” says Cardenas, the family friend and old political ally. “Noelle is leading a normal life.”

When Jeb Bush was exploring whether to run for president in 2016, he said that one of his two major considerations was whether it was “right for my family.” The Miami Herald had reported as far back as 2011 that Columba was on board with a future presidential run, and given who Jeb is, it couldn’t have been the first time she’d considered the possibility. In October of last year, Jeb told the Associated Press that his wife was “supportive” of the idea. Still, throughout the fall, the sense that she was holding on to a veto lingered. Then, in February, The New York Times reported that over Thanksgiving, which the family celebrated in Mexico, “Mrs. Bush gave her approval—though not before winning her husband’s promise to spend some time every week with her and their children and grandchildren.”

The problem with this abbreviated version of the story is that it makes Columba sound like a lobbyist, or like Jeb—quick, decisive, a hard dealer. Friends say the process unfolded more organically, and poignantly. After the couple left the governor’s mansion in 2007, they lived a relatively normal life for the first time in many years, with no security, no public schedule. A few years into that period, Jeb began to soften. Previously when friends saw Jeb socially, there was “a time limit, and when it was done, it was over,” Towey told me. “He’d get his game face on and get back to work.” But in the past few years he would linger. Towey recalled a birthday dinner this year that lasted two hours, where Jeb was happy to have his grandkids crawling over his lap, helping him blow out the candles. Towey got the sense that the couple had grown closer and that Columba had had the space to realize “that he wasn’t just a political junkie.” Ironically, that’s what made her more comfortable with the idea of a presidential run. “It’s not like she was saying ‘Ooh, ooh, run,’ but she loves him, and she could see, just as he would never do it at her expense, she would never say no at his expense.”

Early this year, Columba had lunch at the Biltmore Hotel in Miami, where Jeb likes to golf in the early mornings, with Bart Hudson, the president of the Florida House, the only state embassy in Washington, D.C. Hudson had worked with her when she was the state’s first lady, organizing art exhibitions, and they have remained friends. Hudson politely asked after her husband, as he always does, and she said something unusual. Jeb, she said, was “an artist at what he does,” Hudson told me. “That’s the highest compliment she can give someone,” he said. “It means that she appreciates the depths of what he does.”

Hudson didn’t say whether Columba talked about what a campaign might mean for her—whether she was mourning the loss of their brief spell as private citizens, was bracing herself, or had found a way to look forward to the experience. In 2006, toward the end of Jeb’s tenure as governor, while editing a column about immigration that his office planned to submit to The New York Times, Jeb directed his staff not to mention his wife, even though she is what most connects him to the issue. By 2013, when his book Immigration Wars was published, his attitude had changed. He mentions in the preface the day on the central plaza in León when he met the “beautiful woman with the beautiful name of Columba Garnica de Gallo.” The story is full of campaign-ready clichés—“embrace American values”; “most rewarding experiences of my life”—and it pivots quickly to his position on immigration policy, but still, that early mention may suggest that Columba’s resistance to being packaged for a national audience has melted a little.

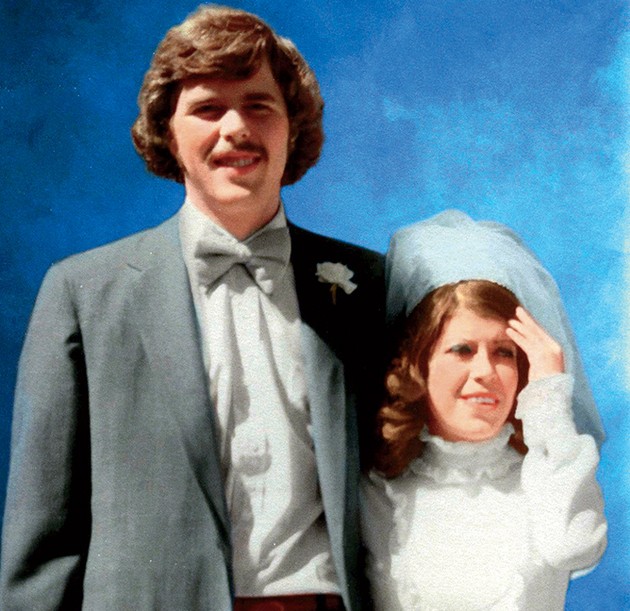

I got the sense from his staff that Jeb is nervous about how Columba will be portrayed in the press. In a correspondence with a reporter in 1999, he wrote, regarding Columba and Noelle, “When they are happy, I am as well,” and I’m sure that’s still true. In February, after the first national news stories in this election season appeared about her and it became clear that the press would not leave her alone, Jeb released an old photo from their wedding—him with floppy hair and a mustache looking like one of the characters Will Ferrell used to play on Saturday Night Live; Columba, 14 inches shorter, trying to look up and at the same time keep the light out of her eyes. Apparently Jeb’s brother Marvin was the wedding photographer and accidentally used rerolled film from a Frank Zappa concert. This picture, taken by Barbara Bush, is the only one from the wedding that came out and survived.

Jeb uploaded the photo to Facebook on their 41st wedding anniversary. Goofy ’70s facial hair, awkward pose, screw-up siblings, no retouching—they look just like the rest of us! And yet it’s hard not to notice that Columba, who must have been happy that day, is not really smiling, but navigating between the blinding light and the gaze of her mother-in-law.

Perhaps, if Jeb becomes president, Columba will get away with a few practiced public speeches and some behind-the-scenes charity work. (She did give a nominating speech in Spanish in 1988 for her father-in-law at the convention in New Orleans.) Perhaps she will get away with letting her sons do the bulk of the talking for the family. Maybe the most interesting thing she could do is create a new model, whereby the first lady does not have to give up being a private citizen merely because her husband is elected president.

Not likely, though. In March, Laura Bush, George W.’s wife, assured voters that Columba will “be great,” telling CNN that she, too, was shy when her husband entered national politics, but got over it. That was partly thanks to a carefully coordinated media strategy to help make Laura comfortable, letting her “practice” first with local print and TV reporters. By the time 9/11 happened, she was ready for the national and international media. “She became the comforter in chief,” recalls Noelia Rodriguez, who was her press secretary at the time. “We just knew it would be very difficult to remain private, because who lives in a private world anymore? Everyone always knows what you’re doing.”

Any decent campaign would package Columba’s immigrant journey as an American triumph, a rags-to-riches fairy tale like the version in Parga’s book. But in my experience, immigrant journeys—even the successful ones—are never that straightforward. Like most immigrants, Columba is pulled between relatives in León who claim she forgot them when she acclimated and relatives in America who want to swallow her whole.

In 1988, George H. W. Bush wrote his autobiography, Man of Integrity, with Doug Wead, and the two discussed possibly dedicating it to his eldest grandson, George P. Bush. Although the boy was all of 11, it was already clear to his grandfather that this son of Jeb and Columba’s would carry the dynasty into the next generation. He ultimately dedicated the book to his wife, but he included a letter to George P. from “Gamby,” in which he imagines little “P” 50 years down the road, out on a rock looking into the ocean. George P. is a Bush through and through; his own young son—Columba and Jeb’s grandson—is named Prescott, after the family patriarch. Columba is a ghost in that lineage.

“I think in life, most of the things are not under our control. My life has been like that,” she told The Miami Herald in 1999. “I try to enjoy whatever comes.”